90 Minutes of TV; 16 Months of Handwaving…

…and counting…

Every day in the UK, £millions are spent on making sure that national and local government departments do not produce too much CO2. Business, schools and hospitals have to make sure they are complying with regulations that require them to reduce their environmental impact – rather than doing business, teaching, and making people well. Commuters across the country face increasing fuel taxes and rising costs of public and private transport. Children are taught to fear for the security of their future, and their parents are scolded for the selfish act of reproducing in the face of over-population. House-builders are forced to meet new ‘environmental standards’, and architects design homes not for their intended occupants’ comfort and quality of life, but to make sure that their living standards are not ‘unsustainable’. Across the media, countless programs, news items, articles, and lifestyle guides instruct us on how we can – and must – change the way we live our lives in a constant barrage of environmental propaganda. Politicians battle about what percentage cuts of CO2 emissions by when will save the planet, and whether the carrot or the stick is the best way to induce behavioural change. NGOs and supra-national organisations dictate policy to democratic governments. ‘Environmental psychologists’ theorise as to what it is about ‘human nature’ which prevents us from obeying environmental diktats. Climate change is the defining issue of our time – not because of incontrovertible scientific fact, but because it has become the organising principle of public and private life.

A mere 90 minutes of programming on Channel 4, nearly a year and half ago, challenged this orthodoxy’s influence. And those behind the orthodoxy have been spitting feathers ever since. It has raised more green bile than almost any other commentary, and has become the scapegoat for the environmental movement’s failure to connect with the public. Accordingly, the environmentalists’ fragile claim to legitimacy means that its first response is to spit invective at its detractors, the second is to run to the censor. What it has not tried is to engage in debate. To do so would be to appear to concede that, in fact, the debate is not over, the science is not ‘in’, and there are various approaches that can be taken in response to climate change, regardless of whether or not humans are causing it.

“It’s not fair!” scream the complaints to OFCOM, that just 90 minutes of program have been so influential, amidst, literally, months of airtime given over to proclaiming that we are doomed, that we face imminent destruction, that unless we change our lifestyles, millions, maybe billions of people will die from plague, pestilence, drought and famine. Never mind that these prophecies themselves lack a scientific basis; you can say whatever you like about the future, just so long as you don’t make the claim that it is not dominated by catastrophe. The most lurid imaginations can project into the future to paint the kind of picture that would have Hieronymus Bosch screaming for mercy, without ever risking OFCOM’s censure. You can make stuff up, providing it will contribute to the legitimacy of this new form of authoritarianism.

The OFCOM ruling on Martin Durkin’s polemic, The Great Global Warming Swindle, was published yesterday. Its findings are that there were problems; that comments attributed to David King – the UK’s chief scientific advisor at the time – were not made by him, even though they were; that the IPCC had not been given sufficient time to respond to comments made about it, even though it had been; and that Professor Carl Wunsch had been misled as to the nature of the program, even though he hadn’t (and isn’t that what investigative journalists are supposed to do?). On the matter of misleading the public, Ofcom found that it had not been offended, harmed, nor materially misled. A mixed review, then, saying, in summary, that Channel 4 were right to broadcast the polemic, but should have paid more attention to the rights of the injured parties. You’d have thought that would be the end of it. But now Ofcom itself is facing criticism from the eco-inquisition, and their decision is to be appealed by Bob Ward, former communications director of the UK’s Royal Society, on the basis that inaccuracies in the program were harmful to the public. Here he is on BBC Radio 4’s PM show:

Eddie Mair: What got you so cross?

Bob Ward: Well, what’s made me angry is the suggestion by Channel 4 that they have been found by the OFCOM ruling not to have misled the audience. And that is not what the ruling says. The ruling says that there were clearly inaccuracies in the programme and that these were admitted by Channel 4, many of them, but, in the opinion of OFCOM, these did not cause harm or offence to the public. Now, I’m afraid that there is no real justification in the ruling that OFCOM have tested whether it caused harm and offence, and actually, there’s quite a lot of evidence out there that it has caused harm, because people have changed their views, I think, about whether greenhouse gas emissions are driving climate change.

EM: And you think that’s down to one programme?

BW: Well, it’s certainly contributed to it, and as Hamish Mykura [Channel 4 Commissioning Editor] was saying, he believes that it’s acted as a lightning rod. It certainly, I mean, people I’ve talked to professionally within the insurance industry with whom I work, some of them have been swayed, and that’s quite damaging. So, as a result, I think it’s certainly true that I and many of the other complainants are now going to appeal against the OFCOM decision on the grounds that there is clear evidence of harm.

EM: Do you think perhaps that some of the complaints that went to OFCOM were too detailed and too technical?

BW: Well, OFCOM did say that they are not there to rule on scientific accuracy, so it’s certainly been a challenge, which is why it’s taken them 16 months to rule. But it’s disappointing that they have reached the conclusions that they have – that although they recognise there are inaccuracies, it didn’t cause harm. They don’t appear to have investigated whether there is harm and how you would justify this. In fact, the OFCOM process is not very transparent itself; it’s not clear how they went about assessing the accuracy of these claims.

EM: Isn’t it true though – and this came over in the interview on The World At One – that while Channel Four obviously broadcast this programme, it intends to broadcast Al Gore’s documentary when it becomes available for television, so a range of views are being represented?

BW: That’s true. And one doesn’t object to a range of views. But there has to be a responsibility among broadcasters not to broadcast factually inaccurate information. That must be against the public interest. And I just don’t accept that broadcasting a programme like this, which was inaccurate about a subject as important as climate change, does not harm the public interest. And that unfortunately is what OFCOM said.

We have argued before that what emerges from the hand-wringing about the few moments of broadcasting that challenge environmentalism is not the exposure of the conspiratorial network of ‘well-funded denialists that environmentalists and the likes of David King and Bob Ward want us to believe exists. Indeed, such shrill hectoring better serves to show the environmental movement in its true colours. The fact that Environmentalists have been unable to laugh off or ignore what they regard as inaccurate tosh speaks volumes about the confidence in their own flimsy arguments. Without the argumentative ammunition to make their case politically, they need to make it into a morality tale. Environmentalists need Durkin and the Swindle like a pantomime needs a villain. They’ve written him into the script. If he didn’t exist, they’d have to invent him.

The Swindle has been made a scapegoat by pollsters Ipsos Mori, Bob Ward and his former boss Bob May, George Monbiot and many others desperate to explain the failure of Environmentalism to capture public hearts and minds. One has to wonder, then, what they hope to achieve by raising the profile of the film. The history of censorship shows that the more noise you make about something you regard as an abomination, the more interesting you make it, and the further you undermine your own position. The reaction to the Swindle has, since we began the blog, led us to look more closely at the activities of the Royal Society, and Bob Ward and co themselves. It turns out that his own position is not so spotless.

In June last year, we recorded Bob May, erstwhile president of the Royal Society, lying to an audience in Oxford about the Swindle‘s director, Martin Durkin. May told the audience that Durkin was responsible for a three part series denying the link between HIV and AIDS, and that this form of climate scepticism was equivalent to denying the link between passive smoking and lung disease. Where were Bob Ward’s complaints about mispresentation and calls for accuracy? It’s hard to believe that May would have made such an error of fact in public, when he publicly demands that we ‘respect the facts‘. All the more ironic is that in counseling us to ‘respect the facts’, he should made several further errors of fact, not least in his translation of ‘Nullius in Verba’, but also in his statement of fact that ’15–40 per cent of species potentially facing extinction after only 2°C of warming’, omitting the fact that this is aworst-case scenario predicted by just a single study. Again, where was Bob Ward and his calls for accuracy? He was busy penning inaccuracies of his own, perhaps. In his open letter to Martin Durkin’s Wag TV, one of Five major misrepresentations of the scientific evidence in the film concerned Durkin’s suggestion that the global temperature slump in the 1950s and ’60s, which was concurrent with rising emissions of greenhouse gases, was problematic for orthodox global warming arguments. Ward asserted that it is established that this is the result of white aerosols masking the greenhouse effect, and yet mainstream climate scientists we spoke to described the evidence for that as flimsy, and said that the debate continues. Another of the ‘five misrepresentations’ concerned Durkin’s argument that solar activity is a major driver of rising temperatures. The science has long been settled, said Ward. So why did the Royal Society find it necessary to publish new research based on a new dataset to demonstrate that the sun was not responsible for global warming after all? And just to make sure we got the message, they even launched the research with the strapline ‘the truth about global warming!‘

All this is not to suggest that the weight of evidence points to the sun rather than anthropogenic CO2 as the culprit. We are more concerned with the double standards employed by the Royal Society and its associates, a body that should surely be standing back from the squabbling and providing cool, calm information about the science in all its glorious complexity. A body that deals in a currency of facts needs to be especially careful about how it wields them. Like a body that bangs on about the dodgy financial interests of ‘deniers’ looks rather silly when its own dealings are on the grubby side of squeaky clean.

So, 16 months after the event, we have a report that says Durkin might have stretched the facts a tad, might have been a bit less than entirely honest with his contributors, might not have been quite as balanced as he could have been. And we are supposed to be surprised? It’s a TV programme. We could have got the same answer from a taxi driver as from a shiny report from an unelected quango. Meanwhile a browse through the pretty pie charts in OFCOM’s carbon audit suggests that the number of plastic coffee cups and notepaper used by OFCOM over those 16 months might have had a bigger negative impact on the planet than any seeds of doubt cast by Durkin’s film. If you think that’s a trivial point, then read George Monbiot’s recent comment on the silly affair, where he asks ‘why does Channel 4 seem to be waging a war against the greens?’.

This ‘War against the Greens’ consists of Durkin’s Swindle, his 2000 film about GM technology (an issue which Monbiot cannot claim the scientific establishment in the form of the Royal Society was with him on) and three-part series in 1997 called Against Nature, and a film by a different producer in 1990. And… errr… that’s it. That’s the extent of this ‘war’. Channel 4 broadcasts 24 hours a day, and has done for most of the past 18 years. Of nearly 160,000 hours of programming, this ‘war’ makes up around five hours; just 300 minutes. Monbiot continues:

It is arguable that no organisation in the United Kingdom has done more to damage the effort to protect the environment

If he’s right, then he’s got absolutely nothing to worry about.

Sceptics and critics of Environmentalism have been portrayed as cranks, weirdos and outsiders. You can make your own mind up about the truth of that. What the reaction to them shows, however, is a deep-seated anxiety which is totally disproportionate to reality. Monbiot and Ward’s paranoid hystrionics about the audacity of Channel 4 and Martin Durkin is nothing short of sheer lunacy. Their hypocrisy and unfounded outrage is breath-taking to an extent that it’s hard to actually conceive of an historical, or even pathological precedent. You would have to be seriously off your rocker to imagine that 5 hours of broadcasting over the course of two decades constituted a war, let alone even a mild threat. The real war – if there is a war, some might dare to suggest that it is simply debate about policy in a democratic society – is a war against journalistic freedom to present Greens such as George Monbiot and Bob Ward as the utter lunatics they really are. Fortunately it doesn’t take documentary films to show this; they do it all by themselves. You don’t need to portray Monbiot as a sinister purveyor of authoritarian misanthrophopy; you can just read his column.

Under the Moon: Gore's Giant Limp for Mankind

Al Gore announced his strategy for powering the USA entirely from ‘renewable’ resources -a mixture of solar and wind – by a decade from now. (Are the sun and wind ‘renewable’? How?)

[youtube dt9wZloG97U]

The ten-year time-span, and the ‘big project’ are borrowed from JF Kennedy’s speech announcing the plan to put a man on the moon. Gore makes no secret of it, indeed, he is overtly trying to capture the same spirit, and sense of historical moment by paraphrasing Kennedy.

But there exist many differences between Gore and Kennedy, and their speeches.

The first is that Gore is not the president of the USA. He’s making grand speeches as though he were. But merely fancying himself as the president of the USA and flattering himself with allusions to Kennedy’s great speeches does not make him either. The question has to be asked; who does he think he is? He has left politics, yet appears to be setting the agenda that even McCain and now ‘Libertarian’ Bob Barr seem to be dancing to. It is a symptom of these times that it is pressure from outside the political process which sets the political agenda. Today’s Western politicians seem incapable of setting agendas, and instead merely respond to the world, hoping that crisis (environment, terror, pandemic, etc) and being in bed with NGOs will lend them legitimacy. Those who attach themselves to the word ‘progressive’ may see Gore’s and environmentalism’s influence on the political process as a Good Thing. But the truth is that, even if they are right about the destructive power of anthropogenic CO2, the political agenda being set so comprehensively by people without mandates is not what happens in a democracy. Gore’s is not an idea which will be contested democratically. It has not emerged from the kind of political activism which used to represent people’s interests, up from the ‘grass roots’. You will notice that Gore has not taken his environmental zeal to the ballot box. If climate change truly were the problem that the world faces, and if there truly were a grass roots mass movement to stop it, the ballot box would be a good place to start ‘saving the planet’. But as European Greens have shown, even weak environmentalism – never mind deep ecology – is simply not popular. What this reveals about politics in the West is that its elites suffer from an unmitigated disconnect with the public. Barr, McCain and Obama cannot challenge Gore, not because Gore has established a transformative political vision and a powerful following, but because they too lack both. In 2005, Gore, citing the disaster in New Orleans, gave a speech around the theme of the proverb ‘where there is no vision, the people perish’. Yet Gore thrives in these circumstances. It is only through being outside politics that he can influence it. It is only by exploiting the widespread cynicism towards politics – rather than by reinvigorating it – that Gore can position himself as a key player. By attaching themselves to this cause, which they sell as ‘above’ politics, presidential hopefuls imagine that they can escape the problems that that cynicism creates for them. His campaign slogan – ‘We Can Solve Climate Change’ – suggests that the impotent political process cannot. It says that ‘by working together, we can make it a priority for government and business’. This small constituency can make a bigger noise outside politics. With hundreds of millions of dollars, rather than people, at his disposal, Gore’s small movement can amplify his message, and achieve the effect of a mass political organisation, without ever actually achieving it.

Gore is not the first to make the claim that ‘climate change is our moon-landing’. In November, 2006, Tony Blair, citing the Stern Report’s findings, told the Royal Society in a speech titled Britain’s path to the future – lit by the brilliant light of science that,

The science of climate change is the moon landing of our day. This is idealism in a technical language. The scientists and the idealists will, once again, be the same people. The discoveries in the laboratory will be matters of life and death. Nothing could be more vital, nothing could be more exciting.

Of course, even Environmentalists do not regard Tony Blair as the saviour of the climate. Their rhetoric may be identical, yet he was not celebrated as an eco-hero by Environmentalists as Gore is. Like Gore, Blair hoped to create a place for himself in history, in spite of his being one of the emptiest voids ever to occupy 10 Downing Street. For example, in one of his most vain moments, following a peace deal made in Northern Ireland, he said ‘this is no time for soundbites, but I feel the hand of history on my shoulder’. Blair’s conceited determination to be remembered as a history-maker was well out of kilter with his ability to actually make it. Lacking the means and opportunities to make history then, Blair, like Gore, merely borrows from history. The subtext of ‘climate change is today’s moon-landing’ is ‘I am today’s Kennedy’. Gore’s and Blair’s speeches, seek not to change the world, but to elevate themselves to the stature of world-changing historical figures. But in Blair’s speech, there is no sign of an understanding of why Kennedy felt that science was key to transcending the political differences which defined the world at the time; he merely uses ‘science’ to create a (bogus) imperative to do so. In other words, science is being used to set, not achieve the agenda. Nor does he offer any explanation as to how and why such idealism had disappeared from the political landscape. Nor does he offer an argument as to how it might be injected back into public life. Blair, like Gore, thought that by presenting the ‘climate crisis’ in terms of the crisis precipitated by the cold war, and presenting the ‘scientific solution’ to that crisis as the means to achieve global cooperation, he would have, like Kennedy, a safe place in the history books. A giant leap. Except that what Gore and Blair have offered is not a political vision of the future powered by science, but merely cargo-cult politics. Like the islanders described by Richard Feynman, who believed that if you performed the rituals that they observed at an air force base, you would bring airplanes loaded with goods to your improvised airstrip, Blair and Gore appear to believe that, to be remembered as a great leader, you just have to go through the motions. But they are poseurs. They put Kennedy on a pedestal, merely so that they can pretend that they should take their place beside him. In much the same way, Blair also likened Saddam Hussain to Hitler, not because he was the leader of an emerging superpower, with the means to execute a global war – clearly Saddam lacked any such power. The purpose of the comparison was to make his part in the morality play – Winston Churchill – more convincing.

The science which Kennedy wished to use to liberate the world from the geopolitics of the time sits in contrast to the ambitions of those who embrace today’s ‘scientific’ conception of the future. It is not the same future. It is a future dominated by an ideology of restraint, of lowered expectations, and of dampened ambitions. Kennedy, on the other hand, had in mind a future of plenty. Today’s politicians instead use science to justify their instructions that we REDUCE! RE-USE! RECYCLE!’ They tell us we are not to use our cars, and that flying is ‘unethical’… unless it is them who are flying, of course. Kennedy wanted to transcend the problems of the age by appealing to interests that people across the world shared, in spite of their differences.

Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths, and encourage the arts and commerce.

Now, however, that pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, commerce, and our common interests are perceived as the problem. Our increasing material liberty has, according to the likes of Blair and Gore, caused the problems that the world faces. Instead of science being used to liberate, it is now to be used to restrain our ambitions, to regulate our lifestyles, and to give a new authoritarianism political legitimacy. In fact, many Environmentalists today regard the moon landing as a wasteful folly, and an environmentally-destructive waste of space.

There is one further, very significant difference between Gore’s and Kennedy’s speeches. Gore’s vision of a ‘renewable’ USA is predicated on the imminent catastrophe which awaits if we do not follow his instructions. It is the gun to America’s head. Kennedy’s plan to send men to the moon had no such basis.

Many years ago the great British explorer George Mallory, who was to die on Mount Everest, was asked why did he want to climb it. He said, “Because it is there.” Well, space is there, and we’re going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there. And, therefore, as we set sail we ask God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.

Kennedy believed that humanity’s common interests and the pursuit of knowledge transcended geo-political differences. Thus, by advancing humanity though science and the arts, and trade, peace might be achieved. In contrast, the folly of trade, arts and commerce are, in Gore’s perspective, the problem. Kennedy’s speech is an appeal to human spirit; Gore’s is a rejection of it. Environmentalism seeks to control human spirit for the ‘higher’ goal of ecological stability. It claims that our interests are, by dint of our dependence on natural processes, second to nature’s. Kennedy asked us to understand nature to use it to our advantage and advancement. Gore asks us to submit to it.

History lends today’s political players crutches to prop themselves up by. Alluding to WWII, public figures demand that we get on a ‘war footing’ to limit our consumption by ‘make do and mend’, as one British public information slogan said. To question this is to demand to be judged by that historical absolute; holocaust denial. To be a denier is, according to the likes of Hansen, to be guilty of ‘crimes against humanity’. The need for such crutches stems from the fact that today’s politicians have no legs to stand on, and environmentalism cannot produce its own history.

POSTSCRIPT:

You could not make it up… Except that someone has… As the post above was being typed, this popped into our inbox from the BBC website:

A “Green New Deal” is needed to solve current problems of climate change, energy and finance, a report argues.

According to the Green New Deal Group, humanity only has 100 months to prevent dangerous global warming.

Its proposals include major investment in renewable energy and the creation of thousands of new “green collar” jobs.

The name is taken from President Franklin D Roosevelt’s “New Deal”, launched 75 years ago to bring the US out of the Great Depression.

The search for historical landmarks by which to give gravity to the climate issue reveals its total hollowness.

Barr Barr Green Sheep

So, Libertarian Party presidential candidate Bob Barr has congratulated Al Gore on his stance on global warming.

Former Vice President Al Gore and I have met privately to discuss the issue of global warming, and I was pleased and honored that he invited me to attend the “We” Campaign event. Global warming is a reality as most every organization that has studied the matter has concluded, whether conservative-leaning, liberal oriented or independent.

Sceptic email lists have been busy circulating messages to the effect that it’s a great shame and a great surprise that a high-profile Libertarian has jumped on the bandwagon. It’s certainly a shame. But a surprise?

As we keep saying, Environmentalism transcends the politics of Left and Right. We are certainly not the first to say that. Many have argued that modern political philosophies fit better along a libertarian-authoritarian axis than a left-right one.

Sure, there’s something very un-Libertarian about Green politics. But Environmentalism is equally incompatible with the old political Left. But that hasn’t stop Marxists or Socialist Workers taking up the cause.

And ex-Republican Barr pushes a rather Rightish sort of libertarianism – an authoritarian version of libertarianism, even. At the very least, he seems rather unsure of his Libertarian values. Barr voted for the Patriot’s Act, for example, although now claims to regret it. He was all for the invasion of Iraq, although now claims to want to withdraw the troops. He takes a very authoritarian line on drugs.

And like all good Environmentalists, he even seems to be under the impression that the appropriate political response follows somehow directly from the science:

Barr, a former Republican congressman from Georgia, said it is time to recognize that global warming “is a very serious problem” and that it will get “dramatically worse” unless significant action is taken.

‘Significant action’? What action? Will it work? Will the cost to our civil liberties be justified? Does ‘action’ mean mitigation or adaptation? His answers to these more important questions are conspicuous by their absence.

The flip side is that there is nothing particularly Libertarian about rejecting the case for anthropogenic global warming. After all, it’s only science. It would be perfectly reasonable, theoretically, for a Libertarian to assess the evidence and come to the conclusion that global warming is happening and that human activities are to a degree behind it. Indeed, we wouldn’t have too much truck with that argument ourselves.

The issue is not whether or not global warming is happening, or is anthropogenic or ‘natural’ (although that is an issue); it’s how that evidence is handled politically. And this is where Barr starts sounding like all those other Green opportunists out there:

“There obviously is a role for government,” Barr said. “There’s a role for private industry. There’s a role for nonprofits and certainly a role for the American people, individually and collectively.”

Barr’s green epiphany, like John McCain’s before him, has less to do with a realisation that they can no longer ignore the weight of scientific evidence, and more to do with a need to be seen to stand for something – anything – at a time when they can’t remember what they stand for anymore.

The US is now in a situation where its top three presidential candidates have subscribed to Gore’s Inconvenient Truth. That is surely a ‘shame’. and yet the ‘surprise’ is that the few sceptics that remain in mainstream politics object to Environmentalism for negative rather than positive reasons. All they know is that they are not Environmentalists. Rather than mounting a political case against Environmentalism, they can resort only to dismissing the movement as a leftist conspiracy and/or to rejecting outright the science that Environmentalism hides behind. We suggest that that is because mainstream climate sceptics are as directionless politically as McCain, Obama and Barr. And it’s little different in the UK. But such negative politics bodes ill for the sceptic movement. Because people don’t vote for what you are not. At Climate Resistance we believe that Environmentalism needs opposing regardless of what the science says. So who do we vote for?

In Praise of Unsustainability

We’ve mentioned before that everything that humans have ever done has been unsustainable. And not in a bad way.

According to architect Austin Williams, sustainability is ‘a philosophy of low aspirations, miserablism, petty-mindedness, parochialism, sanctimony’. Ben has reviewed Williams’ new book The Enemies of Progress: Dangers of Sustainability over at Culture Wars.

The idea of ‘sustainability’, at first glance, has some footing in common sense. To disagree with it seems to mean standing up for unsustainability, defending houses that will collapse: who would be mad enough? Architect Austin Williams’ new book, The Enemies of Progress: Dangers of Sustainability, offers a snapshot of the sustainability’s increasing influence, and gets beneath the sustainable agenda to reveal its true character and aim…

Read the rest of In Praise of Unsustainability here.

BBC On Bad Acid Trip

The merest sniff of an environmental problem can go straight to the heads of the soberest of science reporters and leave them mumbling jibberish about the imminent end of the world as we know it.

Take last Thursday’s edition of BBC Radio 4’s normally excellent Material World, presented by the normally excellent Quentin Cooper, who introduced the programme thus:

Today: acid drop in the ocean. It’s predicted that within this century our oceans will be more acidic than they have been in 55 million years – the time of the last major mass global extinctions. So what will it mean for the denizens of the deep and for ourselves? We’ll examine the results of the first full-scale study of how acidification affects marine ecosystems.

If only they had examined the results, we might have been spared the spectacle of the station’s flagship science programme twisting an elegant, important, yet preliminary, study into a ‘portent of doom’ and concluding that the world’s coral reefs are screwed unless we stop burning fossil fuels.

Many computer models and lab experiments have investigated how oceanic absorption of CO2 reduces the pH of the water, and the effect of such changes on various marine species. As pH declines, so too do levels of dissolved calcium carbonate, with which corals build their skeletons and molluscs build their shells. It is estimated that 40% of anthropogenic CO2 has been absorbed by the oceans, resulting in a decline in ocean pH of 0.1 over the last century, which corresponds to a 30% increase in hydrogen ions (pH is measured on a logarithmic scale). Models suggest that mean pH might drop by up to 0.5 by 2100.

Jason Hall-Spencer‘s research, published a week earlier in Nature (subscription required), is the first to explore the effects of so-called ocean acidification on an ecosystem scale. It focuses on a site in the Bay of Naples in the Mediterranean where CO2 bubbles through the water from volcanic vents in the seabed. While the mean pH of the oceans is about 8.2, around the vents it can be as low as 7.4.

By recording the species composition of reefs along a pH gradient, Hall-Spencer et al found that, the lower the pH, the more impoverished the reef flora and fauna:

Along gradients of normal pH (8.1–8.2) to lowered pH (mean 7.8–7.9, minimum 7.4–7.5), typical rocky shore communities with abundant calcareous organisms shifted to communities lacking scleractinian corals with significant reductions in sea urchin and coralline algal abundance. To our knowledge, this is the first ecosystem-scale validation of predictions that these important groups of organisms are susceptible to elevated amounts of pCO2. Sea-grass production was highest in an area at mean pH 7.6 (1,827 matm pCO2) where coralline algal biomass was significantly reduced and gastropod shells were dissolving due to periods of carbonate sub-saturation. The species populating the vent sites comprise a suite of organisms that are resilient to naturally high concentrations of pCO2 and indicate that ocean acidification may benefit highly invasive non-native algal species. Our results provide the first in situ insights into how shallow water marine communities might change when susceptible organisms are removed owing to ocean acidification.

In an accompanying News & Views article (subscription required) in the same issue of Nature, biological oceanographer Ulf Riebesell, who was not involved in the research, describes the work as

a compelling demonstration of the usefulness of natural CO2 venting sites in assessing the long-term effects of ocean acidification on sea-floor ecosystems, an approach that undoubtedly needs to be further explored […] Our understanding of the processes that underlie its observed effects on ecosystems and biogeochemistry is still rudimentary, as is our ability to forecast its impacts. There is an urgent need to develop tools to assess and quantify such impacts across the entire range of biological responses, from subcellular regulation to ecosystem reorganization, and from short-term physiological acclimation to evolutionary adaptation.

For anyone after their next fix of ecotastrophe, however, a preliminary study can easily become a harbinger of disaster:

Quentin Cooper: So, Jason, if we’ve established that the ocean are becoming more acidic globally, and we’ve looked at these effects and seen that they have detrimental effects on sea creatures, and we also know the predictions are that we’re heading towards the same kind of conditions that we had 55 million years ago, at the time of the last mass extinctions, this all sounds like the key elements for a major portent of doom.

Hall-Spencer did not disagree:

Yes, it doesn’t look good for coral reefs, that’s for sure. Because even for relatively small drops in pH, the corals that we studied in the area dissolved really quickly at this site when we moved them in from outside the area. And so, I was a bit sceptical of some of the science that was coming out predicting these things, because they hadn’t tested it in the real world. But when you go to a place that has been acidified for thousands of years and see what’s been happening, it really does ring alarm bells.

Also in the studio was ocean biogeochemist Toby Tyrrell. He didn’t disagree either. Despite the programme’s promise to scrutinise the results, nobody thought to mention the fact that good reasons to doubt whether the experimental system is a representative model for future reductions in ocean pH had been raised by Riebesell in his Nature commentary:

But there are considerable differences between such systems and the situation arising from global-scale ocean acidification caused by rising atmospheric CO2.

For example, because the vent system effectively comprises an island of low pH, and because it occurs in shallow water, the site is subject to wildly fluctuating variations in pH. On very calm days the pH declines, but on very rough days it remains high. Those fluctuations could themselves be the cause of problems with organisms’ physiology rather than the low pH per se. It could hamper adaptation to low pH, which might otherwise be expected were conditions more constant. Adaptation might also be hindered by the fact that organisms will be migrating in and out of the vent system.

Fortunately there is scope for comparative work, because Hall-Spencer’s study site is not the only CO2 jacuzzi out there. Dive operator Bob Halstead provides pictures of a similar vent system in Papua New Guinea, where CO2 bubbles through what appears to be perfectly healthy coral reef. Of course, these pictures in themselves prove nothing. Indeed, Hall-Spencer told us:

I’ve got some pictures of corals that occur in the Mediterranean with bubbles going up straight past the colony. But when you measure the pH of the water, it’s not dramatically reduced because there’s only a few bubble streams.

He was nevertheless intrigued by Halstead’s example:

If those reefs are surviving low aragonite and low pH conditions then that is definitely cause for optimism about the world’s tropical coral reefs and would be an exciting scientific breakthrough. [But if] the pH is low there due to the CO2 bubbling, then that’s really important, and somebody should go and have a look, because that would refute what we’ve found […] We need to go out there and measure the chemistry of the water […] I’d love to check that out. If there are a lot of bubbles coming up, and there’s hard coral there, then it’s likely that my study is flawed.

As for the comparison with the state of the oceans 55 million years ago, it is true that the high-end projected rise in ocean pH within this century is in the same ball-park as that found during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), when many species were driven to extinction. But correlation and causation are, famously, not one and the same. The PETM extinctions cannot be attributed to the reductions in pH. It was also very hot at the time; the deep oceans were deprived of oxygen; and there was likely a reduction of deep sea turbulence. All of these factors have been implicated. It is not even known what triggered these various changes. The release of massive quantities of methane into the atmosphere as a result of volcanic activity over the space of a millennium is one possibility. And so is the ubiquitous asteroid impact. Intriguingly, the rate of carbon release (in the form of methane) into the atmosphere during the PETM was similar to the rate at which we are pumping it out today as CO2. But if we’re still emitting that much carbon in a hundred years, let alone 1000, we’ll eat our chuddies (which will be very dirty by then). And no, that’s not because the Environmentalists will have got their way, but because we will have found a new, improved alternatives for generating energy by then, despite the efforts of Environmentalists.

Anyway, the PETM is mentioned in neither Hall-Spencer’s paper nor Riebesell’s commentary. Hall-Spencer told us that the connection was Cooper’s own, in order to ‘prick people’s ears up.’

The agreement between the members of the Material World panel even extended to what needs to be done about the looming disaster:

QC: And if we are hearing those alarm bells, what do we do?

JHS: I think we need to use oil less quickly – so these price hikes are good in a way – and look towards wind, wave and tidal power.

QC: Any other suggestions to add, Toby, in terms of practical solutions? Because we’re already getting lots of people advising things along those lines and manage to ignore them. Is this something that people are going to pay more attention to?

TT: Yeah, unfortunately, in terms of avoiding ocean acidification consequences, we have to really look at curbing emissions. There have been some rather outlandish proposals such as taking the white cliffs of Dover and crumbling the chalk there – adding very large quantities of chalk to seawater to neutralise the acid, but really, they are not feasible to any practical degree, so I think we really need to look at stopping emitting CO2.

Less impractical than fiddling around with wind power and rationing energy? Now that’s impractical. Burn less fossil fuels and it’s gonna be harder to save the coral reefs if they really are in peril. Strangely, when we spoke to Hall-Spencer, he said that carbon capture was probably the most realistic option.

So what has happened here? How can a 15 minute feature on a dedicated science programme not only fail to consider problems with a study that have already been flagged up by an expert in the field, but also fail to scrutinise the results or even the politics of the scientists?

Coral biologists have long been pottering around working out how reefs work physiologically, ecologically and biochemically. Nice work if you can get it. Now, suddenly, they have a higher justification for their research. Coral biologists suddenly have an audience. When we suggested this to Hall-Spencer, he said:

I’m very pleased that it’s getting the attention it is, because it allows me to study something that I find fascinating and worrying. So I’m very glad that there’s this head of steam built up and that the funding is there.

He is also under the impression that when scientists get on the radio, they can can stop being scientists and let their hair down:

When you’re interviewed, you can give your own personal point of view, but when you publish a paper that goes up for rigorous peer review, then it’s got to have the caveats and everything else.

And they’re not even going to get challenged, apparently, even on BBC Radio 4. The result is that all the public gets to hear is the story without the caveats. It’s just too easy for all concerned to resort to trying to scare people into action. Much harder is to make your scare stories believable. It does, however, seem to work on opportunistic politicians and funding agencies. And that makes it all rather moreish.

Polls Apart

One of our major gripes with Environmentalism concerns the claims made by its adherents that it is some sort of popular, grass-roots movement. Time and again, polls suggest otherwise. And yet these polls are rarely, if ever, reported in terms of the undemocratic nature of Environmentalism as it is foisted upon reluctant electorates. Rather, they are presented as evidence that the public are unthinking, selfish morons brainwashed by scheming ‘deniers’.

Of course, everybody – ourselves included – will jump on a poll that can be used to support their own position. Which is why Green activist and winner of the Royal Society’s prestigious prize for popular science (fiction), Mark Lynas, picked up on last week’s ICM/Guardian poll. Writing in Comment is Free, he suggests that, in contrast to previous polls, it

shows that a clear majority favours government action on the environment v the economy, while an even larger majority supports the introduction of green taxes.

And it does, if you believe that the answers to such leading questions as ‘Generally speaking would you support or oppose the introduction of green taxes, designed to discourage things that are harmful to the environment?’ tell you anything at all about public opinion.

But, his main point is that the poll dispels the myth that concern about climate change is a luxury of the middle-classes:

perhaps the most fascinating result of all emerges from the small print of the different social classes of the ICM survey respondents. Environmentalists are constantly accused of being middle-class lifestyle faddists, who don’t understand the day-to-day financial pressures faced by “ordinary” working people. But the number of people who thought that environment should be the government’s priority rather than the economy was substantially higher (56%) among the lower income, less well-educated DE demographic than among the better-off ABs (47%). Lower-income social groups also have a much lighter environmental footprint overall: only 42% of DEs took a foreign holiday over the last three years, whilst 77% of ABs did. Better-off people also own more cars, as you might expect – only 5% of DEs have three or more cars, whilst 15% of ABs do.

So perhaps anti-environmental class warriors like the editors of Spiked need to find a new cause to champion. The working-class people who they claim “can’t afford to be concerned about climate change” actually care more about the future of the planet than the rich – and are doing a lot less damage to boot. So next time you hear someone defending motorway expansion or cheap flights on behalf of the British poor, ask yourself the question: whose side are they really on?

Environmentalism might not be popular, you see, but at least it’s equally unpopular across society. Lynas’s view of the “working-class people” has more to do with the idea of the Noble Savage than solidarity with those at the bottom of the social pile. In his world, poverty is something to aspire to rather than alleviate. It’s as if they cause ‘a lot less damage’ as a result of a desire to live in harmony with nature rather than the fact that they are, by definition, less able to afford the luxury of foreign holidays and cars.

Not that we should be surprised. After all, this is the same Mark Lynas who believes that alleviating poverty should be put on hold until the planet has been saved:

The struggle for equity within the human species must take second place to the struggle for the survival of an intact and functioning biosphere

Moreover, Lynas’s attention to the ‘small print’ was not as attentive as it could have been. Otherwise he could not have reached the conclusion that he did. Yes, the responses of DE and AB respondents are comparable across the survey, but the demographics of the two groups suggest that there are good reasons for that that have little to do with social class per se. For example, 50% of the DEs were retired, as opposed to 24% for ABs. Only 18% of DEs were working full time, as opposed to 56% for ABs. And 67% of DEs were not working at all (ABs = 30%). In other words, a much higher proportion of DE respondents are unlikely to be affected by environmental tax hikes.

Lynas’s true sentiments about the masses are evident in his reply to commenters who dare to challenge his latest rant against climate change ‘deniers’:

Well I have to say that most of the comments this piece (and many of my others) has attracted simply prove my rather depressing conclusion that a lot of probably very decent people have swallowed the line pumped out by industry-funded US conservative think tanks. Almost ever denialist argument I’ve ever seen first made an appearance courtesy of them – there’s very little in the ‘denialisophere’ (apologies) which is in any way original.

None of the citations of course mention the peer-reviewed literature, where there isn’t any discussion of whether anthropogenic global warming is real or not, because all the systematic data shows that it is. But it’s pointless to go on digging trenches – and personally I’ve got better things to do than engage with entirely close-minded people. This is a political debate, not a scientific one, and has been for a long time.

Those ‘very decent’ yet ‘entirely closed-minded’ members of the public get the blame whenever polls suggest that they are not giving environmental issues the attention they should be. For example, we reported on last year’s Ipsos Mori’s poll, which found that the majority of people are not convinced that the scientific argument for action on climate change is clear-cut. Report author Phil Downing described the results as ‘disturbing’ and ‘frightening’:

Given the actual consensus and the reality if the situation, it is a particularly disturbing statistic and does suggest one or two things. Firstly the impact of contrarian and negative messages, for example, Channel 4’s great Global Warming Swindle are having an impact. Secondly, if the public is ambivalent, and you have a disconnect between what you believe on the one hand, and how you act on the other. The easiest thing is to change what you believe, rather than how you act.

We thought these sounded more like the words of an opinion former than an opinion pollster.

A couple of weeks ago, Ipsos Mori produced another report along similar lines, which was reported exclusively by the Observer newspaper:

The majority of the British public is still not convinced that climate change is caused by humans – and many others believe scientists are exaggerating the problem

And whose fault is that?

There is growing concern that an economic depression and rising fuel and food prices are denting public interest in environmental issues. Some environmentalists blame the public’s doubts on last year’s Channel 4 documentary The Great Global Warming Swindle, and on recent books, including one by Lord Lawson, the former Chancellor, that question the consensus on climate change.

We spoke to Downing, on the phone and by email. He told us that, when he used words like ‘frightening’ or ‘disturbing’ after last year’s poll, he was speaking from the perspective of the government who had commissioned it. He also said that any mention of the Swindle and Lord Lawson in the Observer article did not come from him. And anyway, he only mentioned it last year because several poll respondents cited the Swindle when talking about their doubts over the government line.

Phil Downing: [W]hen we released the report last year, we did comment that we had started to note in purely qualitative terms that people were making reference to that programme, or had picked up on some of the secondary press […] So we were saying this might be playing a role because this was the first time we were picking it up. But we see it as more of a correlation in time rather than a causation. We have no evidence of a direct link between The Great Global Warming Swindle, or any other programme for that matter, and what is driving people’s views […] We have no quantative data on the extent to which it is driving it. No one has commissioned research to gauge the impact of The Great Global Warming Swindle or An Inconvenient Truth and how the public are making sense of these different messages.

Regardless of who made that argument in which year, however, it boils down to the point that it is democracy itself – a free press, debate, and the need to win legitimacy for political ideas by contest – that has beset the environmental movement’s intentions. Never mind the vast resources available to the Greens to push their own agenda. The fact is that the Observer can count on the fingers of two fingers the number of public challenges to environmental orthodoxy, yet Environmentalism is pushed down our throats from nearly every Government department, local authority, NGO and charity, every current affairs program on every TV channel, in every school, and, according to this article in the Shields Gazette, by Downing himself:

Keynote speaker Phil Downing, head of environmental research for Ipsos Mori, will be encouraging councils to ‘think global’ but ‘act local’ and use the regional advice and support available to inspire their communities to help tackle climate change.

So the question is whether Phil Downing and Ipsos Mori are activists or researchers, opinion pollsters or opinion-formers. We doubt that were he taking such a side on a party-political issue he would be allowed by his employers to make such statements. It suggests that environmental orthodoxy has been established within a certain influential strata of society, who believe it to be ‘above’ politics, as though environmentalism weren’t a political ideology.

Downing told us that the line between pollster and activist is one that he is careful not to cross. And that the Shields Gazette got it wrong – he was there simply to deliver an analysis of public opinion on climate change. If anyone out there happened to attend the event, we’d love to hear from you.

Climate Resistance: Do you have strict guidelines at Ipsos Mori about not crossing that line?

PD: Yes, it’s something that is strictly frowned upon, if you go into something contributing to one side of a debate and not the other […] there are stringent quality control procedures in place to ensure impartiality at Ipsos MORI – this extends both to the way the questions are asked as well as any material we release into the public domain. A specific and in-house team is required to sign off survey materials. As well as the interpretative text we have published the results in full on the website.

Readers can make up their own minds as to whether Ipsos Mori, in blaming a contrarian tv documentary for the public’s divergence from the government line while failing to consider the possibility that the government’s line just isn’t very convincing, should perhaps have another look at their guidelines.

CR: Is it not more likely that the reticence of the public to take up the governmental line on climate change is the result of an unconvincing governmental message?

PD: Well, you’re more than welcome to commission a poll from us.

CR: What would that cost?

PD: Depends. If you’re looking at 1000 people, nationally representative, you’re looking at something like £700-1000 per question.

You could almost understand – if not excuse – the failure to consider the strikingly obvious if, say, the government had commissioned it, because, apparently, you get what you pay for with these things. But, intriguingly, the latest poll was not actually commissioned by anybody. Downing said that Ipsos Mori conducted it off their own backs to shed light on the complexity of the public’s attitudes and beliefs towards climate change. And yet, all it has achieved is to restate the fact that the public is ambivalent, and spawn newspaper articles that seek simplistic excuses for that finding.

To a large extent, there’s little point complaining. Everybody knows that polls are not to be taken seriously; that they are frequently spectacularly wrong; that busy people are keen to fob pollsters off with the answer that is expected of them, etc etc. And, to repeat, we are as guilty as anybody of jumping on poll results when it suits us. When push comes to shove, there’s only one type of poll that counts, and that’s the type that is conducted at the polling booths. And elections demonstrate quite clearly how unpopular Environmentalism is with the masses. The Green Party has no MPs in the UK Parliament, and the Green contingent of MEPs voted into seats in the European Parliament comprise just 5% (and the European elections have a notoriously low turn-out).

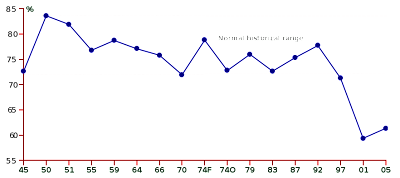

But even more telling is the spectacular decline in the number of people actually bothering to vote:

Funny how turn-out plummets as awareness of the ‘most pressing challenge of our time’ goes through the roof.

Forget the opinion polls. Contrary to the claims of Environmentalists, few people have really bought into their world-view. If anything, most people are slightly irritated by it. Environmentalism persists only because few people object vehemently to it, and because it’s as good as impossible to vote against it.

It's All About Ethanol

Poor old Gordon Brown:

More than 80 Labour MPs have signed an amendment to the Climate Change Bill, which would force ministers to promise greater cuts in carbon emissions.

The Climate Change Bill commits the government to make at least a 60% cut in CO2 emissions by 2050. The MPs want that figure to rise to 80%.

The rebels say the 60% goal will not do enough to control global warming.

This is the latest installment not only in Brown’s Prime Ministerial nightmare, but also in the razor wars that masquerade as environmental politics in the UK. Looking on the bright side, we’re right on course to collect on our prediction that somebody, sometime soon, is going to pledge that the country will be carbon negative by 2050.

Even more predictable is the excuse that the backbenchers offer for their rebellion:

[The rebels] also claim it is based on out-of-date science.

These figures aren’t based on science at all. They are plucked from the thin air of our ailing stratosphere and given authority merely by the use of the word ‘science’ in close proximity.

It all makes the negotiators at the G8 summit seem so last week:

World leaders say they will aim to set a global target of cutting carbon emissions by at least 50% by 2050 in an effort to tackle global warming.

Only 50%! Ach, they’ll get the hang of it. Especially with the G5 developing nations snapping at their heels:

Mexico, Brazil, China, India and South Africa challenged the Group of Eight countries to cut their greenhouse gas emissions by more than 80% by 2050.

Not to mention that bastion of objective, detached scientific investigation, the IPCC’s chairman Dr Rajendra Pachauri, who complains that the developed countries should be showing leadership on such matters:

“They should get off the backs of India and China,” he told reporters in the Indian capital, Delhi.

“They should say: ‘We’ll assist you to move to a pattern of development which is sustainable, low in terms of emissions intensity. But we as the richest nations are willing to take the lead and we affirm our commitment to do so.'”

But the G8 statements on carbon emissions have been eclipsed by discussions of the global food crisis and biofuels, and the supposed causal connection between the two. The G8 pledge to ensure that biofuel policies are compatible with food security comes in the wake of the leaked World Bank report that the push for biofuels accounts for 75% of the food crisis by competing with food crops for agricultural land. Suddenly, it seems, all the world’s problems are less about oil than they are about ethanol.

But, in Food price rises: are biofuels to blame?, James Heartfield provides such anaemic thinking with a healthy dose of red-blooded realism:

For more than 20 years now, both the US and the European Union have pursued policies designed to reduce food output. They have introduced policies that reward farmers for retiring land from production (such as the EU’s set-aside and wilderness schemes). At the same time, the United Nations has used its aid programmes to penalise African farmers who try to increase yields with modern fertilisers or mechanisation […]

The programmes of land retirement and reservation have been so successful worldwide that between 1982 and 2003, national parks grew from nine million square kilometres to 19million, 12.5 per cent of the earth’s surface – or more than the combined land of China and South-East Asia. In the US more than one billion acres of agricultural land is lying fallow. So the idea that land has been lost from ordinary crops to biofuels is not really true; rather, it has been lost from agricultural production altogether.

For the environmentalist critics, blaming biofuels is a desperate act of scapegoating. For years now, they have been propagandising against mass food production, favouring a return to less efficient farming methods, and for the return of farmland to its natural state. It was environmentalists who lobbied for the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future, that biased UN programmes against modern farming techniques in Africa (in favour of ‘appropriate’, which is to say poor ‘technologies’). Just when it suited large-scale agriculture to wind down output to protect prices, the environmentalists were on hand to support land retirement schemes. Farmers, according to Britain’s Countryside Agency, would no longer farm, but become stewards of the countryside.

It’s interesting, then, that the G8 summit has also committed to fulfil a pledge to raise annual foreign aid levels by $50bn by 2010, of which $25bn is intended for Africa. Not that that is a Bad Thing in and of itself, of course; it just depends how it is used. If it’s spent on more of the same, and if similar strings are attached, we can expect more land to be taken out of agricultural production in the name of the saving the planet, more food shortages, more scapegoating, and more tin-pot explanations for why the world is screwed and we’re all going to die. As we keep saying, Environmentalism is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A major question remains regarding the green U-turn on biofuels. Why did Environmentalists ever push the bloody things in the first place? OK, so they are, theoretically, a carbon-neutral source of energy. So far, so green. But the fact remains that it was hardly rocket science to work out that they would necessarily jostle for space with agricultural land and wilderness areas.

So please indulge us while we speculate wildly, and quite possibly wrongly… Could it be that those who were pushing biofuels at the start of the century were figuring that, come 2008, primed by the Green Great-and-Good, the world would have moved on to debating how best to go about reducing the human population to more ‘sustainable’ levels? And let’s face it, if there’s one thing that Environmentalism doesn’t like it’s humans – especially lots of them. And you can bet that, while Environmentalism is not the conspiracy that many of its critics accuse it of being, its adherents do have some sort of long-term strategy. While Gordon Brown, his backbenchers, Tory leader David Cameron and pretty much everybody else in parliamentary politics grasp desperately and opportunistically at Green policies in the absence of any other, better ideas, we at least know where we stand with environmental idealogues such as Jonathon Porritt and Paul Ehrlich (who are both, as it happens, trustees of the Optimum Population Trust, a group for whom ‘optimum’ means – in case you hadn’t guessed – ‘much smaller’).

The trouble is that they underestimated the humanity of, well, humanity. The fact is that in 2008, and despite the efforts of Porritt, Ehrlich et al, the vast majority of us remain repulsed – and may we remain so for ever more – at the thought of population control, just as we remain repulsed by the notion a moral equivalence between nature and civilisation. The result is that they have had to think again.

That said, we are keen not to fall into the trap of painting a simplistic, one-dimensional picture of Environmentalism. There has always been a significant element of the movement that is against the dealings of big-business – especially big agri-business – as a matter of principle. But at the same time, other greens have appealed to market forces in the fight against ecological meltdown. (To repeat ourselves again, Environmentalism transcends traditional Left-Right distinctions.) In which case, the whole messy business might be the product of the push-and-pull between these various Green factions. A bit like the Labour Party, perhaps.

Infinite Regress

In a recent post, we looked at some of Green MEP Caroline Lucas’s arguments for action on climate change. One of them has stuck with us as especially absurd, and merits further attention:

this planet has finite resources. You cannot go on growing indefinitely on a finite planet.

This appeal to ‘physics’ pops up frequently in environmental debates. Interestingly, it’s a tactic also popular with Creationists and their ilk, who cite Newton’s second law of thermodynamics to suggest that evolution contradicts fundamental physical truths. In each case, a woolly argument about how the world should be is patched up with sciency-sounding facts, figures and laws. This is not the tactic of groups confident about their political position; it is a sign of the desperation of groups that are failing to capture the imagination of the world’s population.

In Lucas’s world, the appeal to physics is used as an argument against economic growth and technological development. It is principally a criticism of capitalism, which requires growth and is, therefore, inherently environmentally destructive. It is worth repeating a point we made at the time. The objection to capitalism on the grounds that it contradicts physical laws is a departure from prior objections to capitalism from the Left and is not a criticism of the kind that we would expect the Left to produce. Instead of offering a description of social problems – for example poverty – arising from the social relations produced by capitalism, Lucas seeks to explain social phenomena in terms of geological and biological processes. This is similar to James Garvey’s claims in The Ethics of Climate Change, which appeals to scientific authority to make a case for environmental determinism. In Lucas’s argument, there is a causal chain, from capitalism, via the natural world, to social problems such as poverty, which can be described ‘scientifically’.

Lucas might argue that she could hold both positions simultaneously. But if that were the case, why would it be necessary to emphasise the environmental aspect, let alone mention it at all, given that the social, human-centric perspective is a lot more powerful? The major reason is that the two perspectives are irreconcilable. One looks at social problems as the product of social relations, the other looks at social problems as the consequence of exceeding ‘natural’ limits – ‘unsustainability’. They are further contradictory because we can conceive of non-capitalist growth which is, in the green lexicon, ‘environmentally unfriendly’, but which produces a social good – we could build dams, relocate cities away from coasts, reclaim coasts, create ways for the developing world to have much cheaper access to energy and industrialise agricultural production, and so on. We can also conceive of capitalist growth that is environmentally destructive and yet produces a social good. After all, it’s not as if cars and labour-saving devices and all that stuff have no utility and have been foisted upon people against their will. And it’s not as if economic and technological growth has occurred against a backdrop of lower living standards and declining indicators of social progress. On the contrary, things have got better and better. Lucas – who is unable to make the argument that things are worse in order to challenge capitalism – needs to make the argument that things are about to get worse, and that development of any kind is necessarily environmentally destructive, and so creates a haunting spectre of ‘unsustainability’ and imminent social, ecological and economic collapse.

In this respect, Lucas does not offer us a principled objection to capitalism – she claims that it is wrong in the same way that arguments against gravity would be wrong. Whatever your thoughts about capitalism happen to be, and even if you still believe that environmentalism is a continuation of socialism, it is worth recognising environmentalism’s distance from the traditional Left. It highlights the Left’s political exhaustion, and the environmental movement’s intellectual bankruptcy.

On a similar note, it is not true that notions of sustainable development are antithetical to the economic Right or capitalism. After all Malthus, on whose ideas Lucas’s are based, was a classical economist, whose ideas were debunked by Marx himself. More contemporary conservatives have also embraced the rhetoric of ‘sustainability:

The Government espouses the concept of sustainable economic development. Stable prosperity can be achieved throughout the world provided the environment is nurtured and safeguarded. Protecting this balance of nature is therefore one of the great challenges of the late Twentieth Century

The second problem with Lucas’s argument is that her conception of ‘resources’ is itself flawed. Malthusians – especially environmentalists – misconceive resources as ‘substance’. In a finite universe, never mind a finite world, all substances are of course finite. If our ‘dependence’ on Earth’s resources are ‘unsustainable’ because they are finite, then so too would our much more real dependence on solar, wind and tidal power, be ultimately unsustainable. They are not merely unsustainable in the sense that one day the sun – which drives all renewable sources – will collapse, they are also unsustainable because continued and increasing dependence on this form of energy itself cannot be sustained against growing numbers of people – there is only a limited amount of recoverable energy entering the system at any time. According to environmentalists, this is why we must therefore limit the number of people and ration the amount of energy they are entitled to. We are in favour of some of the large projects which have been conceived of as part of a ‘post-carbon economy’ for their own sake, particularly the idea of large, solar energy collecting arrays. Covering the uninhabited land of the Sahara with solar panels, for example, might provide 50 times the power used currently across the globe. But such projects, including hydro-electric, are met by environmentalists with anxiety about the environmental destruction that large scale developments necessarily cause. And, as we have seen, Environmentalists are against environmental destruction, even where it produces a social benefit.

And anyway, development itself is not intrinsically bad for nature. First, as economies develop, they are inclined to pay increasing attention to the environmental effects of development as wealth allows. Compare the once filthy development in the West to the comparatively cleaner industries of today. Even the destructive process of open-cast mining reinstates wilderness. Indeed, yesterday’s open cast mines are today’s nature reserves. They are clean ecological slates on which Mother Nature can work her magic of colonisation and succession, and are often home to rare, specialist species that are not found elsewhere. Similarly, landfill sites are recovered and repopulated with trees, and what’s more, nobody would want to develop on top of them, whereas nature hardly cares. Second, technological development allows for the possibility of moving away from a dependence on natural processes, resulting in a reduced industrial footprint as both science and economics permit. It would not require a leap of imagination to consider the shifting away from rural agriculture, to an indoor process, under perfect conditions. The reason for not doing that now is that ‘solar power’ makes using fields for crop production far cheaper. But a more abundant form of power would render such forms of production obsolete and inefficient. Of course, organic food faddists would baulk at the idea of lentils grown indoors. But such a step would create the possibility of safer, healthier, more plentiful food, protected from pests and other natural problems, and, of course, would be environmentally non-destructive. This would be a ‘green revolution’ second to none, as agricultural land would be freed up for other uses, including, if we so wished, nature conservation. What environmentalists should be calling for is a world-wide push for new ways of producing more and more energy, and more wealth, not arguing that it should be rationed and limited. Rationing is a guaranteed way to cause environmental problems. That they don’t reinforces the idea that Environmentalism is less about saving the planet per se and more to do with a discomfort with human aspirations.

Access to substance and its existence in sufficient quantities are only part of what constitutes a resource. The remainder is intellectual. Lucas herself must recognise this to some extent, because, as she knows only too well, methods such as domestic solar panels are not currently economically viable alternatives to centralised, fossil-fuel power generation. She argues that huge investments and massive infrastructural changes are needed to develop technology, and for the economics to be adjusted to make alternatives viable. So in this respect, solar energy and other renewables are not yet the ‘resources’ that she hopes them to become. So Lucas’s argument for renewable resources to be exploited in place of fossil fuels is predicated on a transformed relationship with a substance, and the development of the technology to make that exploitation possible. She cannot deny, then, that politics – as much as physics – are what determines which substances are resources.

Back to Lucas’s blind faith in the laws of physics… 500 years ago, oil was not a resource. Neither was uranium. People around at the time didn’t know how to use them. Things that weren’t resources became resources. Our ability to use new resources made old resources obsolete. Now, no home in the UK needs to burn wood for heat, for example. Or, as Bjørn Lomborg has put it, the Stone Age didn’t come to an end because we ran out of stones. What Malthusians forget is that development begats development. After all, you don’t make a jump from rubbing twigs together to atomic energy. Critics of this perspective on this site suggest that this represents some form of contemporary Lysenkoism – that blind faith in science’s ability to rescue us from future resource depletion is a dangerous, politically-motivated folly. They argue that science will not be able to continually provide ‘techno-fixes’ to the problems which emerge from our ways of life. We must come up against some ceiling sooner or later, the logic goes.

But anxiety about ‘growing indefinitely on a finite planet’ forgets that our abilities to make use of the finite space and finite resources increases the effective space and amount of resources that are available. And there is a colossal amount of space, and an abundance of resources out there. For example, we hear a lot about the looming ‘water wars’ that are to be fought because of apparent shortages. A quick look at any map will reveal that the Earth isn’t running out of it any time soon. The problem is simply technological. Instead of concerning themselves with how to provide for a growing population by coming up with desalination, distribution and irrigation schemes, the environmental movement instead uses the prospect of conflict to arm its arguments in favour of restricting development and of rationing what water comes our way through natural processes. What better way could there be of guaranteeing a ‘natural’ disaster than limiting the supply of resources – super abundant resources, never mind oil – to human populations? Environmentalists simultaneously warn of shortages, yet stand in the way of developing any alternatives that might not last ‘indefinitely’. There is only one way out of the resource-depletion scenario that is presented, they say, reduce the number of people, and the amount of resources they are entitled to.

What environmentalists refuse to consider is what a resource- and energy-abundant society might be like. What if stuff in the world just got cheaper? What if access to water and energy wasn’t an issue for anyone in the world? Perhaps, just perhaps, it is this very democratisation of resource use that the environmental movement is a response to. The possibilities that are opened up by technological development for our way of life and our politics are the real locus of anxieties about the future.

Environmentalists demand an impossibly high standard. Nothing the human race has ever done to improve its conditions has been ‘sustainable’. As technologies have changed our lives, and created new problems, so too have new politics arisen out of these changing conditions. If this process had been stalled during any era on the basis that it was unsustainable, we would still be living in stone-age conditions, with stone-age politics – at least, that is, until we really did run out of stones.

The Ethics of 'the Ethics of Climate Change'

James Garvey didn’t like Ben’s review of his book on Culture Wars. But instead of responding to it, he seems to have merely laid out the same argument again.

Science can give us a grip on the fact of climate change. (For a start, have a look here: http://www.ipcc.ch/). We know that temperatures are rising; the sea level is rising too; sea ice is thinning; permafrost is melting; glaciers are in world-wide retreat; ElNino events are becoming more frequent, persistent and intense; and on and on. We know that our fellow creatures are already suffering as a result of climate change. We know that human beings are suffering too and that they will continue to suffer. The Red Cross argue that as of 2001 there were as many as 25 million environmental refugees, people on the move away from dry wells and failed crops. That’s larger than the number they give for people displaced by war. One sixth of the world’s population gets its water from the melting snow and ice tricking down from frozen sources which are likely to dry up in the years to come. There is a lot of suffering underway and on the cards. It’s this suffering which makes climate change a moral problem.

Again, Garvey defers the understanding of the problem to ‘science’, and directs us to the IPCC. There are two main problems with this. First, the IPCC is not beyond scientific challenge as Garvey suggests it is. Second, the imperatives seemingly generated by that scientific definition of the problems – even if the science is true – do not follow necessarily from it. Yes, we may well be inducing climate change, but there may be – in fact, there is – a moral argument that places industrial and economic development over mitigation, in spite of its effect on the environment. Garvey just doesn’t get it. But science cannot and must not be allowed to generate moral and political imperatives. To allow it to do so is to undermine Garvey’s own discipline. In doing so, the best he can offer from moral philosophy is a reduction of complicated scientific, political, and economic arguments to facile comparisons of ‘business as usual’ to ‘standing around, watching a child drown’. Garvey’s inconsequential and trite prose isn’t moral philosophy, it is just standard moral posturing.

But, if Garvey wants to wave science around as a moral weapon, let us look at his understanding of the ‘science’. He says that “we know that…”

“… temperatures are rising”.