Battle of Ideas 2014

The Institute of Ideas‘ tenth Battle of Ideas festival is taking place next month at the Barbican Centre in London.

If you’re not familiar with the event, the Battle is a weekend of many debates and discussions on many different matters, led by speakers from around the world. The Saturday line up is here, and the Sunday line up is here.

I will be discussing Kindergarten culture: why does government treat us like children? with Chris Snowdon, Dan Hodges and Martha Gill. The debate is not about climate change, though it touches on the excess of the climate debate that have been observed on this blog, as well as in many other areas of public life. From the Battle of Ideas website:

In the past, government may have intervened frequently in the economy, but our private lives were our own to live as we saw fit. In recent years, however, government has largely given up on being the ‘hand on the tiller’ of the economy and intervenes regularly in once-private aspects of life. Smoking is now banned in most public places, and smoking in cars in the presence of children is about to be banned. Environmental concerns have led to new efficiency standards for domestic appliances, and smart meters may regulate our electricity usage from afar, while we are constantly told to reduce our consumption of everything and there is serious discussion about how procreation should be limited to save the planet. Even now, parents are increasingly lectured to about how they should raise their children and, in Scotland, the Named Person rules mean a specific government employee will oversee each child’s upbringing.

Even non-governmental organisations, charities, voluntary associations and academics increasingly see it as their role to ‘educate’ ill-informed, non-expert adults. From public health to environmental campaigns, the assumption is that left our own devices, we will make the ‘wrong choices’. England’s chief medical officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, complains that ‘three quarters of parents with overweight children do not recognise that they are too fat’. How can we trust adults who don’t understand the impact of their gas-guzzling family car on the planet or that feeding their kids junk food is leading to an obesity epidemic?

While such attitudes and interventions are viewed as annoying or threatening in some instances, few people actively protest against them. And often there are popular demands for more regulation and legislation to protect us from harm. Why has government become so keen to make decisions for us? And why do we not even seem to take ourselves seriously as autonomous citizens? Or is such ‘infantilisation’ actually a sensible response to our limited capacities and propensity to shoot ourselves in the foot, based on a recognition that in fact, ‘there are no grown ups’. Is it reasonable to allow the ‘experts’ to decide how we live? If not, what should we do about it?

Readers here may be particularly interested in the following sessions…

Tim Worstall, Rob Lyons, Miguel Veiga-Pestana and Amy Jackson will be debating Feeding the world: can we engineer away hunger?:

TV images from Ethiopia in the 1980s seemed to confirm the gloomy prognosis that many parts of the world faced mass starvation. Since then, humanity’s capacity to feed itself looked to be increasing well. China’s dramatic economic growth eradicated hunger for millions, much like the earlier Green Revolution in India. World population has gone up by 50 per cent, yet the proportion of people who are undernourished has fallen dramatically. But gloomy voices of modern Malthusianism are making a comeback, warning that disaster was merely postponed.

[…]

So, can we feed the world in the future? Will the future of food require a radical overhaul of our contemporary diets or can technological and social advancements aim to provide (much) more of the same? Should we look forward to a future of healthy bug burgers edging out the Big Mac, or can innovation and food engineering deliver pleasurable diversity as well as sustenance? And what is the right balance between technological innovation and social development?

Then Dr Alan Walker, Dr Keith MacLean, Rob Lyons, Paul Ekins and Gemma Adams will be discussing Energy futures: how can we keep the lights on?:

Could Britain soon be facing blackouts? Over the past few years, EU rules have led to the closure of many coal-fired power stations. But after much prevarication by politicians, the generating capacity to replace these stations will not be available immediately. For the second half of this decade, the gap between peak demand and total power-station capacity will be close to zero. While much discussion focuses on increasing energy efficiency, the need to increase the absolute amount of energy available is still an urgent priority.

[…]

Is it a positive development that a practical question such as energy production has become such a public hot potato? Are barriers to generating more sources of energy political, technical or environmental? If increased energy can be is secured, will it boost human prosperity by helping fuel economic growth, or will it simply accelerate the destruction of the planet? Can we make a positive case for increased energy production against a backdrop of disquiet about effects on the environment and ambivalence about economic growth per se? How much power should we produce, where should it come from and what methods should be used to produce it? How can we satisfy competing demands, contested priorities and keep the lights on?

Andrew Orlowski, Steve Rayner, Bryony Sadler and Peter Sammonds will be asking After the floods: can we tame the weather?

Are critics right to imply human beings are still a long way from being able to control and withstand the fearsome whims of Mother Nature? Do the most effective forms of flood defence lie in adapting to the landscape rather than adapting the landscape for human habitation? Is it simply common sense that any large-scale attempts to modify the weather or climate come at an unacceptably high risk to future generations of ‘blowback’? What do the weather wars reveal about our attitudes to risk and innovation today?

There are many other discussions on offer, so please take a look. Tickets can be bought at the Barbican website, here.

A note of caution if you’re not buying tickets through the links above… The Battle of Ideas is now a decade old and thus must expect some low quality imitations. As testimony to the Guardian group’s ability to form original ideas and content, The Observer is running its own ‘Festival of Ideas‘ at the same venue, a week earlier. So if you’re buying tickets, make sure you’re buying them for the BATTLE, of ideas, not the Observer’s knock-off.

Stern's Turn

Way, way back in the 2000s, when everyone believed in Hockey Sticks, the UK’s Labour government commissioned somebody nobody had ever heard of to write a report on the economics of climate change, so that it could make an argument for domestic and international political action. The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change has been, ever since, cited in debates about climate policy, the world over, and Nick Stern has become the climate alarmist’s chief guru.

There are many hundreds of pages in the Stern Review. But the detail was abandoned, the review became famous for its simplest and most compelling argument:

Using the results from formal economic models, the Review estimates that if we don’t act, the overall costs and risks of climate change will be equivalent to losing at least 5% of global GDP each year, now and forever. If a wider range of risks and impacts is taken into account, the estimates of damage could rise to 20% of GDP or more.

In contrast, the costs of action – reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the worst impacts of climate change – can be limited to around 1% of global GDP each year.

Stern presented the world with a stark choice: pay 1% of GDP to fix climate change now, or lose at least 5% of GDP in the future.

It is a surprise then, to see Nicholas Stern in today’s Guardian, arguing that growth is now possible:

We can avoid climate change, and boost the world’s economy – if we act now

Reversing the damage is within our grasp, but it will hinge on a strong international climate agreement and policies that make polluters payThe global economy is undergoing a remarkable transformation which is altering our ability to deal with climate change. The growth of emerging economies, rapid urbanisation and new technological advances are making possible a new path of low-carbon growth in ways that were not apparent even five years ago.

Stern’s article does not tell us what these transformations are. A clue is offered in Fiona Harvey’s article on the same:

With all of that scientific knowledge has come technological innovation. Wind turbines were an expensive novelty in the 1980s. Today, several generations of the technology later, they can compete with fossil fuels in generation capacity and on cost. Solar panels have dropped in cost so rapidly that they are economically viable without subsidy in many regions, even those not blessed with constant sunshine. Even fossil fuel-burning power plants have become more efficient, and electric cars provide an alternative to gas-guzzlers, while better building design and more advanced electrical equipment mean we can enjoy modern facilities without rising emissions.

If this is the extent of the technological change, it is underwhelming. Wind turbines cannot compete with fossil fuels in either capacity or cost. As pointed out in the previous post, the entire UK’s wind fleet does not match the output of the coal fired (now converted) Drax power station in Yorkshire. And to make them and other renewable techniques viable, the UK government have committed to subsidising them at least up until 2020. See page 7 of the UK’s new energy market rules here.

Under those rules, onshore wind generators will receive £95 per MWh in 2014/15, dropping slightly to £90 in 2018/19. Offshore wind will receive £155, dropping to £140. In the best case, this doubles the cost of electricity. And this does not yet take into consideration the cost of intermittent wind energy, which rises as the scale of deployment rises. Ditto, the ‘rapid’ drop in cost of solar PV still leaves operators receiving £120 per MWh today, falling to £100 in 2018/19. Even if solar PV could produce energy at the same price as fossil fuels, they would only be ‘competitive’ with fossil fuels if you had no need of electricity at night. There are still close to zero reliable and ‘sustainable’ despatchable techniques for providing baseload and load following. As I argued a few months ago, solar energy’s evangelists are mathematically illterate.

Stern and Harvey’s articles come in the wake of a new report, which Harvey introduces as follows:

Sounds familiar? The New Climate Economy report, co-authored by Nicholas Stern, is published on Tuesday but it echoes the warnings first set out in stark terms in his landmark review of the economics of climate change in 2006. Then, his findings were revolutionary. Naysayers had argued that climate change was just too big a problem, too expensive to solve, requiring as it does an overhaul of the world’s energy systems and economy. Stern proved – in language that economists can understand – that it could be done, that dealing with climate change need not cost the earth.

Harvey, like her Guardian colleague, George Monbiot, re-writes the history of the climate debate. As is explained above, Stern did not debunk the notion that climate change was inexpensive, he argued that it would cost 1% of GDP. 1% of GDP is the difference between modest growth and recession.

The report is available here. The website at least is a triumph of style over substance — if you want to actually find out what the report says, you have to overcome the extremely irritating web gimmicks. Fortunately, searching reveals the download link for a PDF of the summary document here.

On the subject of growth, the report says,

There is a perception that strong economic growth and climate action are not, in fact, compatible. Some people argue that action to tackle climate change will inevitably damage economic growth, so societies have to choose: grow and accept rising climate risk, or reduce climate risk but accept economic stagnation and continued under-development.

Yes, it is a perception that Stern himself created. He said responding to climate change would cost ~1% of GDP. The report continues…

This view is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the dynamics of today’s global economy. It is anchored in an implicit assumption that economies are unchanging and efficient, and future growth will largely be a linear continuation of past trends. Thus any shift towards a lower-carbon path would inevitably bring higher costs and slower growth.

So Stern ‘fundamentally misunderstood the dynamics of the global economy’?

The report then discusses the changes to the global economy that will be experienced in the future, and how the structure of the economy will develop.

But what kind of structural changes occur depends on the path societies choose. There is not a single model of development or growth which must inevitably follow that of the past. These investments can reinforce the current high-carbon, resource-intensive economy, or they can lay the foundation for low-carbon growth. This would mean building more compact, connected, coordinated cities rather than continuing with unmanaged sprawl; restoring degraded land and making agriculture more productive rather than continuing deforestation; scaling up renewable energy sources rather than continued dependence on fossil fuels.

In this sense, the choice we face is not between “business as usual” and climate action, but between alternative pathways of growth: one that exacerbates climate risk, and another that reduces it. The evidence presented in this report suggests that the low-carbon growth path can lead to as much prosperity as the high-carbon one, especially when account is taken of its multiple other benefits: from greater energy security, to cleaner air and improved health.

So Stern has moved from saying that climate policies will cost, to saying that there are no costs.

This reads so far like simply moving the goal posts. Whereas in the mid 2000s, Stern et al emphasised the imperative of responding to climate change — or facing catastrophe — they now want to present global political action as entirely inconsequential with respect to cost. This shift of emphasis is in reality a response to climate advocates’ slow realisation that their alarmism, combined with the fact of costs, merely allowed positions on the climate to become entrenched. One major obstacle besetting global negotiations was the problem of disparity between developing and developed economies: advanced countries would take a bigger hit from a policy, while increasingly wealthy, but still (rapidly) ‘developing’ economies such as China and India would soon be given a substantial competitive advantage. The poorer countries rightly argued that they should not abandon their development, and the richer countries rightly argued that they would damage their own relatively slow-growing economies. The solution offered by anti-growth environmentalists was ‘contraction and convergence’: richer parts of the world would find equitable ways of allowing their economies to shrink until they reached some level of parity with countries coming the other way.

The climate ‘movement’ — such as it is — has always suffered from tension between technocratic green ‘capitalists’ and a scruffier (and no less technocratic) anti-growth contingent. To many sceptics’ perspectives, both camps sought their own elevation by smuggling in under science their rent-seeking impulses or anti-capitalist (respectively) politics. They were right. The nauseating, facile and easily debunked optimism of green capitalists always belied their threat of global catastrophe. And similarly, the equally absurd more left-leaning claims that ‘climate justice’ would end global poverty and war denied the fact that abundant and cheap energy is a necessary (albeit not sufficient) condition for development and actual justice. Climate’s superheroes from both camps have never been able to overcome the possibility that the remedy might be worse than the disease. The maths didn’t stack up. The catastrophic stories just didn’t help formulate policies or encourage agreements. Ends and means became confused, and nobody could agree on either ends or means. The argument for climate action contradicted itself, its proponents disagreed with each other, but blamed the deniers.

The easiest first step in the way out of this impasse is to pretend that climate policies are inconsequential. This requires a pseudo-academic exercise, in which climate researchers pretend to revisit their assumptions. On the way, they produce this kind of monster:

The graphic encourages us, fingers on chins, to nod at the elegant design of this new research. Who knew that solving the world’s problems was as simple as a picture showing the intersection of three vertical arrows pointing towards ‘the wider economy’ with three vertical arrows pointing towards ‘high quality, inclusive and resilient growth’? Those evil climate sceptics had never thought about ‘resource efficiency’, had never been bothered by ‘infrastructure investment’, and never gave a hoot or even talked about ‘innovation’. Now the world’s dilemma presented by Stern is simple: between growth and better growth.

This is made especially weird by the fact that Stern has not, in recent times, been toning down his rhetoric at all. A Guardian article in 2013 quoted Stern,

Nicholas Stern: ‘I got it wrong on climate change – it’s far, far worse’

Author of 2006 review speaks out on danger to economies as planet absorbs less carbon and is ‘on track’ for 4C rise[…]

In an interview at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Stern, who is now a crossbench peer, said: “Looking back, I underestimated the risks. The planet and the atmosphere seem to be absorbing less carbon than we expected, and emissions are rising pretty strongly. Some of the effects are coming through more quickly than we thought then.”

The Stern review, published in 2006, pointed to a 75% chance that global temperatures would rise by between two and three degrees above the long-term average; he now believes we are “on track for something like four “. Had he known the way the situation would evolve, he says, “I think I would have been a bit more blunt. I would have been much more strong about the risks of a four- or five-degree rise.”

At best, Stern is arguing, then, that although the climate is worse than he thought, the possibilities for mitigating those problems are better than he thought. These thoughts, and the development between his thinking in 2006 and 2014 should be laid out more clearly. But instead, we get this, expanding one of the blocks in the above graphic:

Energy systems, which power growth in all economies. Energy production and use already account for two-thirds of global GHG emissions,[27] and over the next 15 years, global demand for energy is expected to rise by 20–35%.[28] Meeting that demand will require major new investment, but energy options are changing. Fast-rising demand and a sharp increase in trade have led to higher and more volatile coal prices,[29] and coal-related air pollution is a growing concern. At the same time, renewable energy, particularly wind and solar power, is increasingly cost-competitive, in some places now without subsidy. Greater investment in energy efficiency has huge potential to cut and manage demand, with both economic and emissions benefits. Taking advantage of new technologies to provide modern energy services to the 1.3 billion people who still have no electricity, and 2.6 billion who lack modern cooking facilities, is also crucial for development.[30]

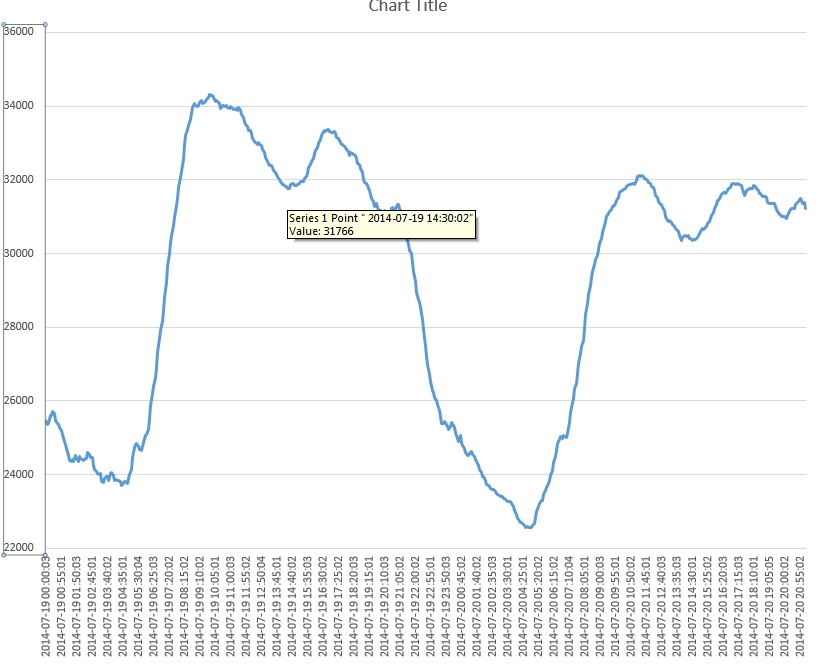

Is the price of coal ‘higher and more volatile’ than it might be?

There have been peaks and troughs, of course — most notably in 2008, when all energy prices rose, thanks to a speculative bubble. Green energy would not protect against such volatility, and given renewable energy’s own inherent volatility, wind and sunshine being subject to Nature’s whims, green autarky might amplify energy price volatility. Hence, ‘demand-side management’, including smart meters open up the possibility of time-of-day pricing. Demand might cause electricity to be too expensive for you to take a shower in the morning, but by lunch time, surplus may be being given away for free. Otherwise, the price of coal looks relatively stable, even falling since 2010, which is offered as one explanation for Europe’s recent increasing use of it. Especially uber-green Germany, where coal use increased from 224,716,000 tonnes in 2009 to 247,526,000 tonnes in 2012. So much for solar panels and wind farms offering competitive alternatives to fossil fuels.

In that same country, the cost of subsidies to renewable operators exceeds 16 billion euros a year. Yet the price of solar panels, says Stern, has fallen. Leaving aside the question of competitiveness for the moment, this creates a further bind for Stern. Had Britain followed Stern’s instructions and Germany’s winding Energiewende back in 2006, it would have the same problems, including energy prices twice what they are now, whereas if policy had been delayed, it would be able to take advantage of a cheaper technology, and committed more to reducing emissions on a £-for-£ basis. Stern was — and still is — adamant that the world cannot afford a wait-and-see policy with respect to climate change, but by claiming that the costs of renewable energy technology have fallen, he defeats his own argument.

It gets worse for Stern. The price of solar panels fell because of European mandates, which created a market for products that European companies could not deliver as efficiently as their counterparts in more dynamic Eastern economies, thanks in part to its own economic stagnation and in turn, of course, to the cost of energy in Europe. The European Commission, which campaigns for global agreements and included amongst its top staff until this month, the climate policy evangelist, Connie Hedegaard, announced in 2013,

The Council today backed the Commission’s proposals to impose definitive anti-dumping and anti-subsidy measures on imports of solar panels from China. In parallel, the Commission confirmed its Decision accepting the undertaking with Chinese solar panel exporters applied since the beginning of August.

In order to prevent dumping of solar panels on EU markets, the Commission has applied a 47.7% import tariff on Chinese panels, rising to 64.9% ‘applied to those exporters who did not cooperate in the European Commission’s investigation’. The irony of all this will not escape readers,

EU ProSun, an industry association, claimed in its complaint lodged on 26 September 2012 that solar panels and their key components imported from China benefit from unfair government subsidies.

Perhaps one of the most heavily subsidised industries in Europe’s history, which had virtually no market before government intervention, complained to the EC that China was subsidising its solar panel manufacturers. This, at a time when, even in the UK, domestic solar panels earned their owners a subsidy worth five times the market value of the electricity they produced.

So much for ‘resource efficiency’, ‘infrastructure investment’ and ‘innovation’, each driven by policy, then. Good or bad, the Chinese got very right what European policy makers — who were hoping to lead the world in green tech — got very, very wrong indeed. They created a market for a product they believed would reduce imports and reduce the volatility of energy prices, but demolished their domestic industry. So much for ‘high quality, inclusive and resilient growth’.

The claim that renewable energy ‘is increasingly cost-competitive, in some places now without subsidy’ forgets that the production of solar panels has been subsidised in a trade war.

On to the report’s discussion about development, in particular that ‘1.3 billion people who still have no electricity, and 2.6 billion who lack modern cooking facilities’. The reference given is to

International Energy Agency (IEA), 2011. Energy for All: Financing Access for the Poor. Special early excerpt of the World Energy Outlook 2011. First presented at the Energy For All Conference in Oslo, Norway, October 2011. Available at: http://www.iea.org/papers/2011/weo2011_energy_for_all.pdf.

It has never been clear to me how renewable energy is supposed to help the poor. And it seems that the IEA, in spite of its recent re-framing as a green energy lobbying organisation did, in 2011, share this point of view.

Achieving universal access by 2030 would increase global electricity generation by 2.5%. Demand for fossil fuels would grow by 0.8% and CO2 emissions go up by 0.7% [over the New Policies Scenario], both figures being trivial in relation to concerns about energy security of climate change. The prize would be a major contribution to social and economic development and help to avoid 1.5 million premature deaths per year.

The New Policies Scenario looks like this:

The 2011 IEA report still bangs on about climate change — climate finance in particular. But it nonetheless shows that there are bigger problems, though perhaps not as fashionable, than climate change. And it shows that climate change might be a price worth paying for development.

It would be great if there were time to pick apart the whole report. But who has the resources — the time and money?

The report is yet another massive volume intended to dominate debate. It sets out an incoherent and badly sourced argument in favour of certain policies, simply to suit the needs of upcoming negotiations. Stern softens his earlier findings, not because there is new evidence, either of a worsening climate or new possibilities of responding to it, but for nakedly political reasons: the desire for an agreement at the UNFCCC COP meeting in Paris 2015, which is looking increasingly unlikely. Having been so instrumental in the failures so far, Stern was the right choice of humpty-dumpty academic for interested parties to commission, as the report explains.

This programme of work was commissioned in 2013 by the governments of seven countries: Colombia, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Norway, South Korea, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The Commission has operated as an independent body and, while benefiting from the support of the seven governments, has been given full freedom to reach its own conclusions.

This explains what Andrew Montford observes today, over at Bishop Hill:

I awake this morning to find my timeline awash with spam from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, furiously retweeting the launch of a report by the New Climate Economy group, a group of green-minded economists headed by Lord Stern and including such eco-figureheads as Ottmar Edenhofer.

[…]

The NCE report, which is here, looks to be very much “more of the same” – renewables blah, investment blah, taxes blah rhubarb blah. I’m more interested in the role of the FCO. Under William Hague’s leadership they look to have adopted a full-on role as eco-campaigners. Which is odd because I thought abusing taxpayers’ funds in this way was DECC’s responsibility.

Clearly, the FCO were involved in eliciting the joint commissioning of other countries. Ethiopia’s GDP per capita in 2013 was US$498. It has nothing to gain by following Stern’s new report.

Moreover, anybody who believes that commissioning Stern does not mean commissioning a report with a foregone conclusion, which suits the political needs of the present negotiations is very daft indeed. Stern gives the game away earlier this year, when he tried to link climate change to the storms being suffered in the UK

The lack of vision and political will from the leaders of many developed countries is not just harming their long-term competitiveness, but is also endangering efforts to create international co-operation and reach a new agreement that should be signed in Paris in December 2015.

In order to manage the perception of the UNFCCC meetings, Stern needed to edit his 2006 review. And SUPRISE! he finds something which is much more palatable.

Enough about the report, what about the organisation which produced it?

The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate,

… is a major new international initiative to analyse and communicate the economic benefits and costs of acting on climate change. Chaired by former President of Mexico Felipe Calderón, the Commission comprises former heads of government and finance ministers and leaders in the fields of economics and business.

The New Climate Economy is the Commission’s flagship project. It aims to provide independent and authoritative evidence on the relationship between actions which can strengthen economic performance and those which reduce the risk of dangerous climate change. It will report in September 2014.

The project is being undertaken by a global partnership of research institutes and a core team led by Programme Director Jeremy Oppenheim. An Advisory Panel of world-leading economists, chaired by Lord Nicholas Stern will carry out an expert review of the work.

We are working with a number of other institutions in various aspects of the research programme, including the World Bank and regional development banks, the International Monetary Fund, International Energy Agency, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations agencies and a variety of other research institutes around the world.

This is yet another inter-governmental organisation, founded without any real mandate, to manage the perceptions of climate negotiations, and to preclude debate.

After publication of its report in September 2014, the Commission will take its findings and recommendations directly to heads of government, finance and economic ministers, business leaders and investors throughout the world in a systematic outreach strategy. The results will be communicated to the wider economic community and civil society through a variety of global and national media channels. The aim is to contribute to global debate about economic policy, and to inform the policies pursued by governments and the investment decisions of the business and finance sectors.

Nobody will ever be accountable for decisions informed by the New Climate Economy. The partners in The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate are all parties with a given interest in establishing global policies. So the authors of the report can be as promiscuous with the facts as they want. Is this not obvious? Take, for instance this page, detailing the profiles of people involved with the project,

Ben Combes is a co-principal on the New Climate Economy with John Llewellyn, working on the macroeconomic programme. Ben has over ten years’ experience working in economics, strategy, and policy. An experienced macroeconomist, he also has extensive environmental economics expertise, across both public and private sectors. Ben spent four years in the UK Government Economic Service working on macro themes: first, on energy and environment at Defra; then on climate change at the UK Committee on Climate Change with Adair Turner (Chair). Before that, he spent three years at macroeconomic consultancies: GFC Economics with Graham Turner, analysing G8 economies; and Oxford Economics. More recently, he led a strategic review of the Civil Aviation Authority’s environmental role for Andrew Haines (CEO). Ben started at Deloitte in audit and advisory. He holds an MA (Hons) in Economics from the University of Edinburgh, and an MSc in Environmental and Resource Economics from University College London. Ben directs work on a number of macro themes, notably demographics, energy, and technology.

And

Michael Jacobs is Senior Adviser to the New Climate Economy, responsible for supporting the Program Director and management team on overall strategy. He is Visiting Professor at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics, and in the School of Public Policy at University College London, and Senior Adviser at the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations in Paris. He was formerly Special Adviser to UK Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown. An economist, he has written extensively on environmental economics and politics.

And

Christoph Mazur is a researcher working on the Transformation of Transport within the Innovation Workstream at the New Climate Economy. Chris is a PhD researcher of the Grantham Institute for Climate Change at Imperial College London, and also a Climate-KIC PhD student. His research on socio-technical systems looks at sustainable transitions in the transport sector, and especially the transition from fossil fuel based cars to hybrid, electric or fuel cell vehicles. Before that he worked as Manufacturing Engineer for Daimler Buses North America and recently finished a fellowship at the UK Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology in Demand-Side Response. Chris has a degree in Mechanical Engineering and Business Administration (RWTH Aachen) as well as Industrial Design (Ecole Centrale Paris). Follow him on: LinkedIn.

And

Daniele Viappiani is Senior Programme Officer at the New Climate Economy, where he is contributing directly to the research on Drivers of Growth while also helping to ensure the overall research programe is sound, relevant and communicated clearly. Daniele is seconded from the UK Department for Energy and Climate Change, where he works as senior economist on International Climate Change. Prior to joining NCE, Daniele held a number of positions on climate change and food security at the UK Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, including as head of the UK government research programme on climate change adaptation. He loves cooking and speaks fluent Italian and Spanish. Daniele has an MPA from the London School of Economics and a BSc in Economics from Bocconi University.

The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate claims its aims are to ‘contribute to global debate about economic policy, and to inform the policies pursued by governments and the investment decisions of the business and finance sectors’. But it is comprised of people already working towards an agenda, simply transplanted from one institution to another. If the climate policy debate were to draw on indefinitely and each person in it were immortal, in not much time at all there would be organisations formed comprising every possible combination of people. It is inconceivable that this organisation would not produce precisely what the British government wanted it to produce, just as it is inconceivable that Nick Stern would produce something inconvenient to upcoming climate talks. It is like asking Charlie Sheen to write a report on the virtues of sobriety and temperance.

Here we see yet another climate institution, manufactured by governments, to produce evidence that they will wave during negotiations in favour of the policies they have already determined they want. Policy-based evidence-making can now be seen as an institutional process. It is an absurd charade, which is made necessary because truly independent research organisations i) no longer exist, and ii) would not write such a document, and there is no trust for the organisations behind the new initiative. Thus it is necessary to produce ‘research’ for the needs of the upcoming negotiations.

This institutional cancer demolishes the distinctions between research, governance, negotiations, business and media. What Guardian hacks say is what self-serving NGO hacks say is what Stern says is what the government commissioned. The people left out of all of this, though, is the public. Political expediency causes a tragic corrosion of the public sphere, a loss of debate, and ultimately the loss of the value of research and science to society. Why bother with the charade?

Monbiot Re-Writes History

Environmentalists don’t understand politics. Especially democratic politics. And Environmentalists aren’t much good at history either. And it should be noted, that although environmentalists like to claim that their perspectives are grounded in science, they are promiscuous with scientific facts: scientific consensus on climate, good; scientific consensus on the risks of GM crops, bad. Those who fail at these subjects are destined to rewrite them according to their needs.

Monbiot! Again! After something of a pause in Monbiot’s climate routine, he is today telling the world what it should be doing:

Stopping climate meltdown needs the courage that saved the ozone layer

Governments dither on the solution to global warming – but the Montreal Protocol is a reminder of a time when they took their hands out of their pocketsThis is how environmental diplomacy works. Governments gather to discuss an urgent problem and propose everything except the obvious solution – legislation. The last thing our self-hating states will contemplate is what they are empowered to do: govern. They will launch endless talks and commissions, devise elaborate market mechanisms, even offer massive subsidies to encourage better behaviour, rather than simply say “we’re stopping this”.

I haven’t noticed the dearth of climate and energy legislation that Monbiot refers to. It seems more likely that the ‘obvious’ solution of legislation is the one which is hastily sought, where in fact it might be the least effective tool. Here in the UK, for instance we were subject to the Climate Change Act, which had been drafted by Friends of the Earth, which won climate activist Bryony (now Baroness) Worthington a seat in the House of Lords. The failure of the Climate Change Act, combined with the economic situation, resulted in a lack of investment in energy infrastructure — a problem now coming home to roost, as the UK faces winter with the smallest ever capacity margin, and Europe being denied gas by Russia — led to the Energy Act (Energy Market Reform), which transfers more risk from investors to the consumer. Since this blog’s first post back in April 2007, the hope of the UK government has been wind power. Yet in that time, the net capacity of wind energy has not increased by the output of just one coal-fired power station, many of which are now closed thanks to… yes, you’ve guessed it… Legislation. Namely, the EU’s Large Combustion Plant and Industrial Emissions directives.

According to Renewable UK, the UK has 7,534 MW onshore wind capacity, and 3,653 MW of offshore capacity. If we multiply these by their typical respective load factors (25% and 30%), we get 2,979 MW of net capacity. Before it was converted into a power station that burned American forests, Drax power station in Yorkshire had a capacity of 3,960 MW, and a load factor of 76%, producing a net capacity of 3,009 MW. It is not enough to simply pass legislation, like some kind of latter-day Cnut, and expect the world to fall into the order it imposes. The market did not have sufficient confidence that wind technology was viable, in spite of the promises of subsidies that could yield as much as 10% on the investment per year. The number of consented wind farm projects grew, yet only half of them were built. It took yet more legislation, “Energy Market Reform”, to ‘send signals to the market’ — Liberal Democrat speak for promises of public money. Meanwhile, the uncertainty generated by so much political intervention, uncertainty and vacillation in the face of growing public scepticism and ire at rising energy prices meant that new conventional plant did not get built, and the hope that the low carbon imperative could revive the UK’s nuclear energy sector forced the government into a deal with EDF for the most expensive power station in the world — at Hinkley Point.

Legislation, then, rather than mobilising resources, can paralyse an economy. Rather than creating the ‘Green Industrial Revolution’ that the Labour and current coalition governments promised, they merely made it much more difficult to build new capacity of any kind in sufficient time either to meet the targets they had set, or to close the energy gap that their incautious policymaking had created.

As Roger Pielke Jr. explained in 2008,

The approach to emissions reduction embodied by the Climate Change Act is exactly backwards. It begins with setting a target and then only later do policy makers ask how that target might be achieved, with no consideration for whether the target implies realistic or feasible rates of decarbonization. The uncomfortable reality is that no one knows how fast a major economy can decarbonize. Both the 2022 interim and 2050 targets require rates of decarbonization far in excess of what has been observed in large economies at anytime in the past. Simply making progress to the targets requires steps of a magnitude that seem practically impossible, e.g., such as the need for the UK to achieve a carbon efficiency of its economy equal to that of France in 2006 in a time period considerably less than a decade.

The failure of the UK’s Climate Change Act was predictable before it had even begun, explained Pielke. And this should take us back to Monbiot.

This is what’s happening with manmade climate change. The obvious solution, in fact the only real and lasting solution, is to decide that most fossil fuel reserves will be left in the ground, while alternative energy sources are rapidly developed to fill the gap. Everything else is talk. But not only will governments not contemplate this step, they won’t even discuss it. They would rather risk mortal injury than open the gate.

‘Leaving the fossil fuels in the ground’, and ‘rapidly deploying alternative energy sources’ are not solutions. ‘Alternative energy sources’ are not actually alternatives, in the sense of ‘alternative’ which makes two things equivalent, or interchangeable. In the past, environmentalists, Monbiot included, were honest about the fact. In 2005, Monbiot said,

The notion that we can achieve this by replacing fossil fuels with ambient energy is a fantasy. It is true that we have untapped sources of energy in wind, waves, tides and sunlight, but it is neither so concentrated nor so consistent that we can plug it in and carry on as before.

And the following year, in Heat, Mobiot said of the climate change movement,

It is a campaign not for abundance but for austerity. It is a campaign not for more freedom but for less. Strangest of all, it is a campaign not just against other people, but against ourselves.

Moniot’s commitment to austerity was owed to what science had determined was a necessity, he claimed. In other words, he knows — he must know, because he has been arguing for years — that there is no equivalent ‘alternative’ to fossil fuels.

This is reflected in official thinking on climate policy. When Pielke published his research, I spoke with Professor Julia King of the Committee on Climate Change:

Professor Julia King, who is both chancellor of the university and a member of the Climate Change Committee, raised an objection to Pielke’s analysis: ‘Before you make statements about timetables and targets which don’t ask “can this be done?”, I think you really do need to take due account of the fact that most people who are putting together targets and timetables are doing this on the basis of a lot of research into potential scenarios. It’s another issue turning that into policy, for governments, and it’s very easy for all of us who don’t have to be elected to say “this is how I would do it”, and I have a lot of sympathy for our politicians, because they are dealing with extremely selfish populations.’

[…]

‘The biggest challenge is actually behavioural change in my view. My particular area has been looking at how we can decarbonise road transport. It wouldn’t take much behaviour change to reduce by 30 or 40 per cent our CO2 emissions from cars.’

King appears to want to sustain her cake and eat it. On one hand, she argues that targets have been ‘tested for do-ability’, but on the other she emphasises that behaviour change is key to meeting them. These targets may well be ‘do-able’ in the sense that they are feasible – we could dispense with all electricity and transport problems simply by ‘changing behaviour’ such that nobody used transport or used electricity. But what kind of society would we have?

This contempt for people creates a problem for Monbiot and for the legislators he now chides. It is not simply a matter of a choice without consequence; reducing CO2 emissions carries serious consequences, even in a country as wealthy as the UK. A global policy on climate change would have to suit people from economies where GDP per capita range between orders of magnitude. While many bloggers have pointed out that this creates a problem which may in fact be bigger than climate change, George Monbiot and his pals have insisted that what we have been doing is in fact ‘denying’ the science.

Political practicality is as much a problem for legislators as technical fesibility. Even a seemingly equitable arrangement whereby the world cut its emissions by 90% by 2030 that Monbiot demanded would leave much of the developing world in its condition of subsistence, and would expand the parts of the world experiencing such conditions. Policymakers from around the world, for all their desires for a global agreement, are not so stupid as to realise that striking such a deal would not result in a terminal loss of their offices, if not leaving them dangling from lamp posts. Legislators are, after all, in most places, appointed by democratic processes.

In other words, legislators need a mandate to legislate. This blog has pointed out, however, that environmentalism is at least as much an attempt to circumnavigate problems of democratic legitimacy as it is a response to environmental problems — that it is easier to take moral authority from scientific experts than it is to elicit from the governed the consent to govern in lieu of a convincing argument. Monbiot’s short cut through democracy — with a bulldozer — demonstrates that democracy and the necessity of debate were never very close to his thinking. It as if he is thinking “WHY DON’T THEY BLOODY WELL JUST DO WHAT I WANT THEM TO DO?“; technical feasibility and political reality not really being obstacles that Monbiot’s ego can even acknowledge.

World leaders have attempted to achieve an agreement, for reasons that I find dubious, but let’s take them at face value here. There was something like legislation — the Kyoto Protocol — which set the framework for legislation in some of the countries which signed up to it. The EU’s emissions-trading system, for instance. There are many and varied reasons cited for the failure, and the subsequent expiry of the Kyoto Protocol, and world leaders’ inability to identify a successor, but the one which should concern Monbiot is that, unlike a sovereign nation, the United Nations does not (yet) have the means to bind countries to ‘legislation’ in the way that parliaments of various kinds can enact legislation. It makes no sense to really speak about ‘legislation’ in this way, agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol are just that, agreements. Treaties take the place of the sovereign, constitution, or whatever institution that the executive of a polity takes its authority from. And in spite of environmentalists’ claims that the world will surely end without an agreement of the kind Monbiot wants, the facts on this are not as certain as has been claimed, and there are simply too many non-convergent interests to bring under one policy.

George Monbiot should understand the failure of the Kyoto Protocol, the reasons why agreements are so hard to achieve, and should be able to ponder the legitimacy of any such agreement. Back in 2004, he wrote a book called ‘Age of Consent: A Manifesto for a New World Order‘. In the manifesto, Monbiot argues that whereas corporate power has been globalised, democratic power has not.

Everything has been globalized except our consent. Democracy alone has been confined to the nation state. It stands at the national border, suitcase in hand, without a passport. A handful of men in the richest nations use the global powers they have assumed to tell the rest of the world how to live. This book is an attempt to describe a world run on the principle by which those powerful men claim to govern: the principle of democracy. It is an attempt to Replace our Age of Coercion with an Age of Consent.

This aim required the construction, or democratisation of global political institutions:

The four principal projects are these: a democratically elected world parliament; a democratised United Nations General Assembly, which captures the powers now vested in the Security Council; an International Clearing Union, which automatically discharges trade deficits and prevents the accumulation of debt; a Fair Trade Organization, which restrains the rich while emancipating the poor.

On the basis that Monbiot knew, a decade ago, that global political institutions have little or no democratic legitimacy, why would he today call for them to impose a policy on the world? What if Monbiot’s global political institutions were constructed, but a fully democratic United Nations determined that the world had other priorities than fighting climate change? I argue that the undemocratic institution, the United Nations that exists now, and its bodies, such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change exist to overcome the problem of democracy: to reduce it. Talk about democratising profoundly undemocratic institutions would be like talking about how to burn coal in order to reduce atmospheric CO2.

Let’s take a step back. What would it mean to construct or convert a global democratic institution? Democracy is not something that can be simply implemented. It is the consequence of many generations’ conflicts and settlements, as weight of numbers took power away from divine right and from military and financial muscle. Democracy has never been given, and is never a given. It has always been fought for, by the people who wanted to represent their own interests or wanted them represented. Thus, in order for there to be a democratic institution, a potential demos must exist, with a demand for the dismantling of an old political order and/or its democratisation. Building a democratic global political institution now would be like building a house from the apex of the roof down to the foundations: it is upside down politics. There is no such mass of people, with such demands.

The concept which makes Monbiot’s 2004 vision unworkable is sovereignty. For better or worse, people understand that sovereignty begins with the individual, and ends at the nation state. The reasons should be obvious: this is, or has been, the way that political institutions and relationships between them and individuals have developed. Various political theorists have observed that authority lies in the implicit consent of the people who observe it. That is not to rule out the possibility of some future global polity necessarily, but that the United Nations and other supranational institutions would never volunteer to democratise, and there is no means by which a mass movement can express its desires to them. It is more likely that political movements would make the decision to withdraw their country from such processes, thereby repatriating power ceded to supranational bodies. People simply have no relationship with the United Nations.

Although organisations such as the UN may have been established for good reasons, in times of deep geopolitical conflict, their mandates and missions shifted. Concomitantly, institutions seek ground to legitimise themselves. Although article 2.1 of the Charter of the United Nations states that “The Organization is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its Members”, the sovereignty of nation states became the thing that caused the problems that the UN was intended to solve. Nowhere is this more evident than in the UN’s machinations on the environment. At the first plenary of the United Nations Environment Programme in 1972, Maurice Strong…

…stressed the need for:

(a) New concepts of sovereignty, based not on the surrender of national sovereignties but on better means of exercising them collectively, and with a greater sense of responsibility for the common good;

(b) New codes of international law which the era of environmental concern required, and new means of dealing with environmental conflicts;

Strong is in Humpty Dumpty territory, of course. In the UK, it is the sovereign’s government which enacts laws, and her Police force which enforces it, and anyone accused of breaking it faces the Crown, in her court. Similarly, in other political systems, defendants face either ‘The People’, or ‘The State’. Hence ‘The People versus…’. The notion, therefore, that one can have ‘international law’ without ‘surrender of national sovereignties’ to at least some (if not total) extent, is pure bunk. An oxymoron.

One claim made in defence of supranational institutions is that national sovereignty — or its unmitigated expression — can cause conflict. After two world wars, how to keep ambitious leaders of nation states in check? But this, apart from presupposing that it was national sovereignty, unleashing irrational and violent forces, which led to war, merely defers the problem. How to keep ambitious Canadian fossil fuel multi-millionaires from becoming UN Commissioners and taking such liberties with language and logic?

In the same way that democracy is never given, bureaucracies swell and seek new ground to accommodate them. Perhaps there are good reasons for global forums, including conflict and environmental problems. But in order for a forum to expand its power, those problems need to be framed as terminal, and beyond the understanding or reach of sovereign nation states. Notice how often environmentalist tend to talk about the impossibility of ‘solving climate change’ within democratic frameworks, either explicitly or by implication. On many green views, democracy merely unleashes material lusts, or forces governments to respond to them rather than the issues that the likes of Monbiot decide should be at the top of the agenda. On similar perspectives, humans are just not psychologically equipped to understand issues or risks beyond their everyday experience. A fat, feckless and fecund public — the ‘extremely selfish population’ — is no longer trusted to count as the body politic; ‘civil society’ fills the political vacuum created between people and government by the elevation of political power to supranational institutions.

Back to Monbiot, who believes that world leaders should be able to solve climate change as quickly and easily as they solved the ozone crisis under the Montreal Protocol.

In 1974, before any noticeable issues had arisen, the chemists Frank Rowland and Mario Molina predicted that the breakdown of chlorofluorocarbons – chemicals used for refrigeration and as aerosol propellants – in the stratosphere would destroy atmospheric ozone. Eleven years later, ozone depletion near the South Pole was detected by the British Antarctic Survey.

The action governments took was direct and uncomplicated: ozone-depleting chemicals would be banned. The Montreal Protocol came into force in 1989, and within seven years, use of the most dangerous substances had been more or less eliminated. Every member of the United Nations has ratified the treaty.

This was despite a sustained campaign of lobbying and denial by the chemicals industry – led by Dupont – which bears strong similarities to the campaign by fossil fuel companies to prevent action on climate change.

Roger Pielke Jr, however, offers us a more thoroughgoing analysis than the simple story of goodies, armed with science, versus baddies armed by vested interests with lies:

Conventional wisdom holds that action on ozone depletion followed the following sequence: science was made certain, then the public expressed a desire for action, an international protocol was negotiated and this political action led to the invention of technological substitutes for chlorofluorocarbons.

In the late 1970s, DuPont was the world’s major producer of CFCs, which it calls Freon, with 25% market share. In 1980, the company patented a process for manufacturing HFC-134a, the leading CFC alternative, after identifying it as a replacement to Freon in 1976. Immediately before and after the signing of the Montreal Protocol, DuPont had applied for more than 20 patents for CFC alternatives. Du Pont saw alternatives as a business opportunity. “There is an opportunity for a billion-pound market out there,” its Freon division head explained in 1988. Du Pont’s decision to back regulation was facilitated by economic opportunity – an opportunity that existed solely because of technological substitutes for CFCs.

Technological advances on CFC alternatives, really starting in the 1970s, helped to grease the skids for incremental policy action creating a virtuous circle that began long before Montreal and continued long after.

In other words, the solution to the problem of ozone depletion — leaving aside questions about the magnitude of the problem for the moment — had a simple technological remedy. Monbiot, however, blames the innovator of solutions for standing against it. The mistake being Monbiot’s confusion about the relationship between corporations, markets and regulation. On Monbiot’s view, corporations hate regulation. But in real life, regulation gives corporations advantages: they are more able to mobilise resources or capital at scale than smaller counterparts. There would be no market for DuPont’s CFC-alternatives without the Montreal Protocol (except in the USA, where CFCs had already been banned). Moreover, many CFC patents were in any case, about to expire, leading to various theories that DuPont may have even been behind ozone legislation. The truth of those claims is immaterial, the point is that Monbiot paints black and white what was in fact a much more complex picture, and now invites us to ask why climate change doesn’t have as simple a remedy…

So what’s the difference? Why is the Montreal Protocol effective while the Kyoto Protocol and subsequent efforts to prevent climate breakdown are not?

Part of the answer must be that the fossil fuel industry is much bigger than the halogenated hydrocarbon industry, and its lobbying power much greater. Retiring fossil fuel is technically just as feasible as replacing ozone-depleting chemicals, given the wide range of technologies for generating useful energy, but politically much tougher.

Monbiot has forgotten his own words…

The notion that we can achieve this by replacing fossil fuels with ambient energy is a fantasy. It is true that we have untapped sources of energy in wind, waves, tides and sunlight, but it is neither so concentrated nor so consistent that we can plug it in and carry on as before.

It is a campaign not for abundance but for austerity. It is a campaign not for more freedom but for less. Strangest of all, it is a campaign not just against other people, but against ourselves.

Either Monbiot is keeping some new-found faith in green abundance, or his preference for green austerity quiet. Either way, clearly he is offering up only a simple message, so he can sustain a story of an easy technical solution, thwarted by the might of the fossil fuel industry’s conspiracy — a conspiracy that Monbiot has much trouble producing any evidence of. The conspiracy theory deepens…

When the Montreal Protocol was negotiated, during the mid-1980s, the notion that governments could intervene in the market was under sustained assault, but not yet conquered. Even Margaret Thatcher, while speaking the language of market fundamentalism, was dirigiste by comparison to her successors: enough at any rate to be a staunch supporter of the Montreal Protocol. It is almost impossible to imagine David Cameron championing such a measure. For that matter, given the current state of Congress, it’s more or less impossible to see Barack Obama doing it either.

By the mid-1990s, the doctrine of market fundamentalism – also known as neoliberalism – had almost all governments by the throat. Any politicians who tried to protect the weak from the powerful or the natural world from industrial destruction were punished by the corporate media or the markets.

Monbiot will note that the Rio Earth Summit was held in 1992, under the stewardship of director general fossil fuel multi-multi-millionaire Maurice Strong (again). No fewer than 116 heads of state attended, each of them, no doubt, were by then entirely gripped by the ‘doctrine of market fundamentalism’. The conference mandated the creation of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, and the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Not bad for a world that Monbiot claims was on the absolute precipice of market dogma.

This extreme political doctrine – that governments must cease to govern – has made direct, uncomplicated action almost unthinkable. Just as the extent of humankind’s greatest crisis – climate breakdown – became clear, governments willing to address it were everywhere being disciplined or purged.

Even though five years later the world according to Monbiot was having its face stamped on by the ‘extreme political doctrine’, ‘neoliberalism’, it managed nonetheless to establish the Kyoto Protocol under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Here is a simple rule of thumb for anyone confused by the claims and counter-claims made in political debates: anyone ever using the term ‘neoliberalism’ is more confused by the world than you are, and no matter how confident their manner is, they are talking bullshit. That is not to defend any doctrine described as ‘neoliberal’; it is just to say that anyone who thinks it is an adequate description of the world since the 1980s is as confused as Monbiot.

And that is an adequate explanation for, as well as a description of, the real dynamic of that era: not so much the ascendency of any ‘-ism’ in particular, but their collapse. Especially the left, and those parts of it which now can do nothing — least of all organise themselves against it — which feebly whine ‘neoliberalism’ at the world, and complain about ‘capitalism’ standing in the way of international agreements which were designed by… capitalists!… who made their fortunes selling oil.

It doesn’t occur to Monbiot that the fundamental failure of international climate institutions and their policies to at least share their objectives, if not implement them, is owed to the fact that, not only are they undemocratic, they are intended to circumvent the problems of post-democratic politics. In other words, green institutions and green global policymaking positively thrived in the era he suggests was dominated by capitalism. As recently as 2008, the UK, without any semblance of real democratic process, passed the Climate Change Act (see above), and more recently Energy Market Reform, even though the terms of these acts go further than anything the UK is obliged to do by its membership of Kyoto, or under any EU directives.

Environmentalists represent the full manifestation of that confusion. Hence one doesn’t need to scratch the surface of Monbiot’s theses (or any other green manifesto, for that matter), to discover its dark authoritarianism. They want order out of what they perceive as chaos: so many fat, fecund and feckless people — the ‘extremely selfish population — not doing as they are told. Authoritarianism speaks to the loss of faith in other people, distrust of institutions, and personal experiences of detachment from the world. It is amazing that a man that has seen so much of the world fails to apprehend it; Monbiot’s moral and social disorientation is projected back out onto the world as a story about environmental catastrophe.

Tackling any environmental crisis, especially climate breakdown, requires a resumption of political courage: the courage just to open the sodding gate.

Mobiot believes that ‘political courage’ means doing things that he wants, in spite of what other people want and the technical or political feasibility of being ‘courageous’. However, he stumbles across a truth here, by accident. He is right that today’s political class is not courageous. But that dearth of courage better explains the phenomenon of supranational institution building, of global agreements, and of political and public individual’s championing of climate change than it explains the failure of those policies as they meet political and technical reality. It is easy for politicians and journalists to attach themselves to global, terminal and invisible crises — easier than it is to face the seemingly trivial, but extant and day-to-day problems. It is easy to claim that the conditions experienced by millions, if not billions of people are the result, not of politics and policies, but of climate change, and to promise that policies which will mitigate climate change will bring about world peace, end poverty and create a general sense of well being amongst all people. It’s easier to dress up as superman, dealing with crises that nobody can perceive than it is to set out a coherent political vision, and to compete with it, against others, to an engaged public. Hence, power is accumulated, above democratic institutions, apparently to save the planet.

That is the opposite of ‘political courage’. Nothing is at stake. No careers are risked, no reputations are put on the line, no power is gambled with. This is why sceptics are vilified — almost the entire political establishment, in its total and utter cowardice, has closed ranks in defence of itself, on the issue of climate change. It fails because it meets political and technical realities, not because there is no ‘ambition’.

Monbiot takes a very cartoonish view of the Montreal Protocol, its history and its scientific underpinnings to make an extremely simplistic political argument. He rewrites history as ‘global policy making is simple; technological solutions are simple; simple baddies stand in the way’. But the Montreal Protocol was in fact the first implementation of the precautionary principle. As the protocol itself states, parties were…

Determined to protect the ozone layer by taking precautionary measures to control equitably total global emissions of substances that deplete it, with the ultimate objective of their elimination on the basis of developments in scientific knowledge, taking into account technical and economic considerations and bearing in mind the developmental needs of developing countries,

Noting the precautionary measures for controlling emissions of certain chlorofluorocarbons that have already been taken at national and regional levels,

Far from proceeding from science, which ‘predicted’ anything, as Monbiot claimed, the threat to the ozone layer from CFCs and its consequences for the natural and human world were theoretical — i.e. unquantified — risks. The precautionary principle allows agreements or policies to be implemented without science providing certainty. The possibility of the ozone layer thinning, just as the possibility of the planet warming, allowed speculation of the kind usually leant to cheap science fiction plots than scientific research. This is not to say that the Montreal protocol — or rather, the objectives of the Montreal Protocol had no foundation whatsoever, but that it was then part of a broader process of seeking a basis on which to ground global institutions, that had been in motion since the 1960s, and that one cannot understand the construction of the Montreal and subsequent protocols, their creation, and the basis of their construction by taking them at face value.

As is reported over at PJ Media, in spite of very recent claims of an ozone recovery, conveniently timed with a celebration of the Montreal Protocol’s 25th anniversary, there is much dispute about the state of the ozone layer.

Within the span of nine months, NASA issued statements claiming of atmospheric ozone that “signs of recovery are not yet present,” there is “large variability,” it is “stabilizing,” and now, that the hole is “shrinking.”

So which is it? The answer may lie in the relevant political science, not the atmospheric. The Montreal Protocol is 25 years old this year, having been entered into force in 1989. When such milestones are reached, there is always pressure to make some statement that the work of the UN actually made some sort of difference.

In many debates about climate change, sceptics have been challenged to criticise the Montreal Protocol on exactly the basis that Monbiot’s argument proceeds, in the hope that once the sceptic agrees the basis for the Montreal Protocol, he will accept the need for The Kyoto Protocol and whatever follows it. In these arguments — and therefore in the environmentalists’ imagination — the science is unimpeachable, and the forecasts of consequences due to ozone depletion as incontrovertible as 2+2=4, and therefore the Montroeal Protocol an imperative — there is no possibility that the sensitivity of ozone was overestimated, no possibility that the consequences of any amount of depletion was overstated, and no possibility that the protocol was successful because a technical alternative to CFCs could be found. The fact of the Monstreal Protocol’s existence seems to stand as conclusive proof of the environmentalists’ presuppositions and claims, both with respect to the ozone layer, and atmospheric CO2.

We can see in the claims made now, and in the past, and made now about the past that the accounts offered by Monbiot are not consistent with the facts — the science, history and politics of the environment are rewritten, to suit the needs of the present. The ozone layer may not have be damaged, much less fixed, yet the role of the precautionary principle has been written out of history. The ozone layer may have been fixed, yet the role of evil corporations finding alternatives to CFCs does not get a mention in Monbiot’s tale of goodies and baddies. Scientists may or may not have identified a looming problem, but Monbiot does not talk about the excessive claims made about the scale of that problem in pursuit of the Montreal Protocol. And the Monstreal Protocol itself may turn out to have done some good, but nowhere does Monbiot, in spite of his concerns about undemocratic institutions run by the super-wealthy, worry about the character of the politics that is being established above democratic governments in the name of the environment, orchestrated by multi-millionaires.

The last words here belong to Geophysicist, Joe Farman, who, while working at the British Antarctic Survey, was part of the team who discovered the hole in the ozone layer.

Well, I mean I suppose I’d better go on record somewhere as pointing out that, please, if you ever read the World Health Organisation’s view of the Montreal Protocol, just don’t believe it. They will tell you that the Montreal Protocol has prevented N cases of eye trouble in the Tropics, and various other things, and the answer is: what on earth do you mean? There hasn’t been any ozone depletion in the tropics, there hasn’t been any increase of UV, documented increase of UV in the Tropics, what the hell has the Montreal Protocol got to do with saving all this vast number of malignant melanomas and the rest of it, you know. And they – and the world goes mad in front of environmental problems and alarmist scares and things like that. It sort of somehow takes the story to be hard evidence and it just, you know. As far as I know no one has yet demonstrated, anywhere in the world, that any harm has been done to anyone by ozone depletion or any organism. All the krill around Antarctica are very sensible creatures; they live under the ice. They’ve got the most wonderful sunscreen there is, you know. And if they’re in the open water, when the sun comes up they go down. Not the slightest evidence that anything has yet changed. And, you know, okay we don’t want to lose the ozone layer, I’m as keen as anyone to get rid of CFCs and put the ozone layer back to where it was. But you don’t fight battles by misleading the public. Once they, you know, get known that this is the sort of which goes on, you can’t even start a story anymore [laughs]. I mean it’s the trouble with climate change: it’s been so overdone, it’s seized on by politicians because it’s a wonderful excuse for getting a wonderful new tax, ‘Save all the budgetary problems, you know, we just put a carbon tax on.’ No way. No way.

A Climate Economics Antinomy

Paul Ehrlich once famously remarked,

Giving society cheap, abundant energy would be the equivalent of giving an idiot child a machine gun.

A point noted here often is that although environmentalists claim that their perspective is grounded in science, their desire for social control is palpable. The criticism that many advocates of climate policies make of climate sceptics is that they are driven by their distaste for regulation. Paul Nurse, for example, told an audience in Australia,

A feature of this controversy is that those who deny that there is a problem often seem to have political or ideological views that lead them to be unhappy with the actions that would be necessary if global warming were due to human activity. These actions are likely to include measures such as greater concerted world action, curtailing the freedoms of individuals, companies and nations, and curbing some kinds of industrial activity, potentially risking economic growth. What seems to be happening is that the concerns of those worried about those types of action have led them to attack the scientific analysis of the majority of climate scientists with scientific arguments that are rather weak and unconvincing, often involving the cherry-picking of data.

Whether or not Paul Nurse is right that ‘climate change is happening’, and that it has consequences for our way of life, he cannot escape the problem that he and his predecessors have sought a greater role for science, and for the Royal Society in public policy. In the foreword to the Royal Society’s brochure for its newly launched Science Policy Centre in 2010, zoologist, Baron John Krebs, said,

Today, scientific advice to underpin policy is more important than ever before. From neuroscience to nanotechnology, food security to climate change, the questions being asked of scientists by policy makers, the media and the public continue to multiply. Many of the issues are global in nature, and require international collaboration, not just amongst policy makers, but also between scientists.

In the run-up to its 350th Anniversary in 2010, the Royal Society has established a Science Policy Centre in order to strengthen the independent voice of science in UK, European and international policy. We want to champion the contribution that science and innovation can make to economic prosperity, quality of life and environmental sustainability, and we also want the Royal Society to be a hub for debate about science, society and public policy.

Krebs is, coincidentally, a member of the UK’s Committee on Climate Change — the panel of allegedly independent experts which decides the future of the UK’s ‘carbon budgets’. Being an expert on birds, he is well placed to set the parameters of UK Energy policy, half a century into the future.

The face-value reading of this ascendency of science in the political sphere is that the world faces a growing number of risks, which can only be understood by individuals with technical expertise. But another explanation of the same phenomenon is that technical expertise is sought because today’s politicians, as managers of public life but lacking the moral authority enjoyed by their predecessors, need them where they previously enjoyed a mandate from the public. The idea of exerts managing the world is an attractive one, but leaves the problem of what it is they are managing it for: what is the agenda, programme, vision? Heaven forfend that experts, like anyone else in positions of power, might be in it for themselves

The problem grows deeper. It is hard to legitimise the elevation of the expert positively. The familiar justification for climate policies — or rather, the construction of political institutions above democratic control — is the doctor analogy. According to this feeble analogy, if you were sick with cancer, you would seek out the best cancer expert you could find to treat you. Thus, the world can only be cured of its ‘cancer’ — climate change — by asking ornithologists how much carbon people in 2040 should be allowed to emit, and by asking genetic biologists like Paul Nurse what is the best form of political organisation. The elevation of experts needs seemingly technical crises: it’s not enough for scientists to discover the means to produce better material conditions for us.

So, about that expertise then…

Skeptical Science’s latest bore-a-thon is the #97Hours project, which is documenting the (literally) cartoonish account of the climate consensus with, erm, cartoons, published every hour… This one caught my eye:

Ken Denman, who studies ‘the interactions between marine planktonic ecosystems, physical oceanographic processes and a changing climate’ has something to say, not just about policy, but the weakness of human will.

The issue is not a lack of scientific evidence, the issue is the unwillingness of people and governments to act. It seems to defy logic. But a lot of addictions defy logic. Our society is completely addicted to cheap power.

‘Our society is addicted to cheap power’, he says, echoing Pauls Ehrlich and Nurse. Leaving aside the fact that Denman’s scietific expertise doesn’t really give him any insight into ‘addiction’, much less the reasons for policy failure, and that this should give us a clue about his understanding of how science should be applied to society, I was also struck by this recent cartoon, published this week, and wondered how it chimes with Ehrlich, Nurse and Deman:

The claims are produced by Cambridge Econometrics for the WWF. Says the WWF,