Climate Sceptics: The Phantom Menace

At the Guardian this week (yes there, again), David Robert Grimes claimed,

Denying climate change isn’t scepticism – it’s ‘motivated reasoning’

True sceptics test a hypothesis against the evidence, but climate sceptics refuse to accept anything that contradicts their beliefs

Grimes, a medical physics researcher at Oxford channels a lot of the guff that is passed off as ‘research’ into the phenomenon of climate scepticism. In particular, Grimes cites Stephan Lewandowsky’s ridiculous, unscientific and poorly-executed magnum opus:

The problem is that the well-meaning and considered approach hinges on the presupposition that the intended audience is always rational, willing to base or change its position on the balance of evidence. However, recent investigations suggests this might be a supposition too far. A study in 2011 found that conservative white males in the US were far more likely than other Americans to deny climate change. Another study found denialism in the UK was more common among politically conservative individuals with traditional values. A series of investigations published last year by Prof Stephan Lewandowsky and his colleagues – including one with the fantastic title, Nasa Faked the Moon Landing – Therefore, (Climate) Science Is a Hoax: An Anatomy of the Motivated Rejection of Science – found that while subjects subscribing to conspiracist thought tended to reject all scientific propositions they encountered, those with strong traits of conservatism or pronounced free-market world views only tended to reject scientific findings with regulatory implications.

Well, if white, male, American conservatives believe something, it must be wrong. Meanwhile, of course, as I and many others have demonstrated, there was a great deal wrong with Lewandowsky’s work. No matter though, because as long as a bullsh*t survey can be turned into an article to be published in a journal, it must be true, no matter the criticism of it… Probably from white, conservative males. The scientific consensus on climate change soon reveals itself to in fact be little more than a social prejudice.

Grimes continues…

It should be no surprise that the voters and politicians opposed to climate change tend to be of a conservative bent, keen to support free-market ideology. This is part of a phenomenon known as motivated reasoning, where instead of evidence being evaluated critically, it is deliberately interpreted in such a way as to reaffirm a pre-existing belief, demanding impossibly stringent examination of unwelcome evidence while accepting uncritically even the flimsiest information that suits one’s needs.

This, of course, is an argument that, in lieu of a perfectly-calibrated mind-reading machine, is unscientific, through and through. Although we might notice that people’s arguments tend to coincide with their preferences, the hypothesis that the preference exists before the reasoning is untestable bunk. Moreover, although it appears to privilege reason, by denying that the objects of the hypothesis are capable of it, in turn deny the value of reason. Even more moreover, positing that one putative side of a debate lacks the necessary faculty to make rational choices forgets the influence of ideology over the counter-position. As I have argued before, if one takes a robust view of individuals faculties, and of course in wider society, one might well take a different view of the scientific evidence. For example, environmental ideologues evince a view of the world which holds that: i) the world is fragile; ii) the world provides; iii) the relationship between the world and people is delicately balanced. Those claims are not scientific. They are presuppositions. They are also, in large part, mystical in origin. And they are categorically anti-human, in the sense that they do not necessarily privilege human experience in their reasoning and in their deeper philosophical ideas (such as they are). It follows that one or two degrees warming is, on one view, fatal, catastrophic. And on the other view, perhaps a problem in particular times and places.

Perhaps it’s not a surprise that a low-rent activist-journalist writes about the other side of the debate in such a way. However, his Guardian profile claims ‘He has a keen interest in the public understanding of science’. No he doesn’t. He wants to use science to achieve a particular political end, and he doesn’t care if he — in the amateur PUS/STS vernacular — ‘abuses science’ and confuses the public in the process. Science is a weapon — a point I will return to later.

Debates, like consensuses, have an ‘object’. Let’s say there is a debate about the proposition ‘all apples are green’. The proposition is the ‘object’. Let’s imagine that all the apples studied thus far are green. Thus, the consensus is that all apples are green’. But some scientists and interested folk take the view that, although all apples are green, there’s nothing about apples that means they have to be green. Carrots used to be purple (I am told). We might one day see a red apple, say the sceptics of the consensus. If you shut your eyes, you wouldn’t notice the difference. The debate, although it is dominated by the consensus view, now divides on a very particular grounds, about which it is very hard indeed to get excited about.

Granted, it is an absurd example. But let’s stick with it. It tells us something about consensuses and debates. They are about something. They are about the colours of apples, or they are about the value of X, or they are about the best way to organise society.

Grimes’s account of the debate, however, does NOT give us any information about the object of the debate. It says this, of course…

The grim findings of the IPCC last year reiterated what climatologists have long been telling us: the climate is changing at an unprecedented rate, and we’re to blame. Despite the clear scientific consensus, a veritable brigade of self-proclaimed, underinformed armchair experts lurk on comment threads the world over, eager to pour scorn on climate science. Barrages of ad hominem attacks all too often await both the scientists working in climate research and journalists who communicate the research findings.

… But to what extent is the debate defined by the claim that ‘the climate is changing at an unprecedented rate’? Is this even the object of the consensus? But worse, what is the counter-position — the claim that sceptics make in response?

The IPCC, of course, do not make quite such a claim. Grimes produces a grotesque and value-laden over-simplification. Of the thousands of lines of evidence evaluated by the IPCC, the response from the sceptics is not, as Grimes would have it, a simple negation of a single proposition, but instead consists of a range of criticisms and questions, about each of them.

Even if Grimes accurately presented the scientific consensus, he still doesn’t explain the debate, because he does not even attempt to explain the sceptic’s counter-position. There is no scientific debate in the world where this would be acceptable to the academic community. Yet this mythology persists, and is sustained, in large part by academics.

Grimes offers a crude, and entirely partial approximation of the consensus, because the extent of the consensus diminishes as it becomes specific. The broad consensus on climate change is inconsequential, thus activists like Grimes need to play fast and loose with it. Notice, for instance, that one account of the consensus (more accurate than Grimes’s) holds that ‘most of the warming in the second half of the twentieth century has been caused by man’, and does not exclude the majority of climate sceptics, who typically argue that the IPCC over estimates climate sensitivity. Moreover, notice that many sceptics do not take issue with the propositions that CO2 is a greenhouse gas, much of the increase in atmospheric CO2 can be attributed to industry, that this warming will likely cause a change in the climate, and that this may well cause problems. One of the biggest debates between sceptics and their counterparts is in fact the role played by feedback mechanisms — a response in part to claims by environmentalists such as Mark Lynas in ‘Six Degrees: our future on a hotter planet’ that a relatively small increase in CO2 could cause ‘runaway climate change’ by triggering (unknown and possibly non-existent) feedback mechanisms to form.

The approximate consensus seems to serve, not inform the debate with science, but to supply it with moral coordinates in the environmental activists favour: you don’t need to know about the mechanics of CO2 or the climate; you only need to know that there are good guys and there are bad guys. To supply the debate with the actual consensus position and counter-position would deprive the moral argument of the utility that ambiguity offers. While it can be claimed that there is an other — an irrational, malign force — acting to subvert the debate, scientists and activists can seem to be on the same team. The moment the debate is deprived of its ambiguity, and supplied with actual data, it turns out that many activists, and indeed, scientists-cum-activists, are far further away from consensus position represented by the IPCC than are the putative ‘deniers’.

So, the ‘consensus without an object’ is a cohesive force. The environmentalists argument does not depend on science as much as it depends on depriving the debate — denying — of science.

This is to say that the ‘consensus’ has political, rather than practical utility: it is more useful to the task of mobilising towards ‘action on climate change’ than it is informing the debate about what kind of problem climate change is, and what the options for dealing with it are.

I have observed this before. In Naomi Oreskes’ work attempting to identify relationships between the ‘tobacco lobby’ and climate sceptics, she proposed that key individuals were ‘Merchants of Doubt’, and employed the same strategy — ‘the tobacco strategy’. As I wrote, back in 2008:

What Oreskes seems to forget is that doubt, rather than being generated by the “denialists”, has long been at the very core of environmental politics. Consider the following statement, which is part of the 1992 Rio Declaration, agreed at the Earth Summit…

Doubt is the very essence of the precautionary principle. And the precautionary principle is at the heart of international agreements and domestic policies on the environment. It was not scientific certainty that drove efforts to mitigate climate change, but the same doubt that Oreskes claims is generated by the “tobacco strategy”. In claiming that denialists were generating doubt where there was certainty, Oreskes – a professor of the history of science – re-writes scientific history. More interesting still, Oreskes seems to agree with the “deniers” that scientific certainty – rather than doubt – should drive action.

[…]What matters to Oreskes is not the substance of scientific understanding, but an isolated, binary fact that “climate change is happening”. From here, “climate change” can mean anything. Once it has been established as a “fact”, it doesn’t matter what science says, because the doubt incubates the imagination better than certainty, and prohibits scientific expertise from undermining the power of the nightmare.

The Precautionary Principle operates just as the ‘consensus without an object’. It is not the facts of the matter that count. To define the problem of climate change means turning climate change into a merely technical problem, rather than a problem in which the parameters can be constantly shifted, for political ends. Oreskes epitomises the phenomenon of mobile goalposts by claiming that the movement which had for so long been grounded in the precautionary principle had instead been formulated on the basis of certainty. Perhaps more fatal for Oreskes is that any debate that seems to proceed from a scientific claim is going to take the form that she describes, of a proposition and doubts about its soundness.

Coincidentally, Lewandowsky and Cook have been channelling Oreskes 2008 work this week, at The Conversation:

So why are tobacco control measures now in place in many countries around the world? Why has the rate of smoking in California declined from 44% to less than 10% over the last few decades? Why can we now debate the policy options for a further reduction in public harm, such as plain packaging or tax increases?

It is because the public demanded action. This happened once the public realised that there was a scientific consensus that tobacco was harmful to health. The public wants action when they perceive that there is a widespread scientific agreement.

The argument defeats itself, of course. The public neither demanded action to stop smoking, and it didn’t demand action on the basis of ‘widespread scientific agreement’. If the public really hated smoking so much, it wouldn’t need the intervention. There is widespread scientific agreement that hitting yours head with a hammer is a bad idea. But curiously, there is no law banning people from hitting themselves with hammers. It is understood, widely, that people’s own sense of self prevents them from hitting themselves with hammers, and that where this faculty fails, there are bigger problems at play. There also existed, for a long time, that even in spite of the known risks caused by smoking, that it was a pleasurable thing for the smoker, and that he or she was capable of taking his own risks. If there was a shift in public mood, it had much less to do with ‘science’ than it had to do with the fact that smoking can be an nuisance to others, and possibly a fire risk in certain environments, and a health risk to people with certain conditions. Lewandowsky and Cook, like Oreskes, re-write history to make a political argument in the present…

A scientific consensus is necessary to understand and address problems that have a scientific origin and require a scientific solution. The public’s perception of that scientific consensus is necessary to stimulate political debate about solutions. When the public comes to understand the overwhelming agreement among climate scientists on human-caused global warming, acceptance of the science and support for climate action increase.

[…]

In a recent article, Mike Hulme argued that the debate “needs to become more political, and less scientific”. We agree, because the scientific debate has moved on from the fundamentals – there is no scientific debate about the fact that the globe is warming from human greenhouse gas emissions. So we need to hammer out political solutions rather than “debating” well-established scientific facts.

Hulme also suggested that, in reference to a paper by John Cook, “merely enumerating the strength of consensus around the fact that humans cause climate change is largely irrelevant to the more important business of deciding what to do about it.”

[…]

When Hulme queries the value of consensus on human-caused global warming in the peer-reviewed literature, he has it backwards in two important ways.

Closing the consensus gap is an important step towards the public debate about climate policy which he rightly calls for. The problem is the attack on climate science and the overwhelming consensus, not the research supporting it.

Straight from the horses mouth… the ‘consensus’ has political, rather than practical utility: The public’s perception of that scientific consensus is necessary to stimulate political debate about solutions.

Lewandowsky and Cook were responding to Mike Hulme’s essay on the same website, ‘Science can’t settle what should be done about climate change’. Hulme was clear about his view of Cook’s attempt to measure the extent of the consensus,

A paper by John Cook and colleagues published in May 2013 claimed that of the 4,000 peer-reviewed papers they surveyed expressing a position on anthropogenic global warming, “97.1% endorsed the consensus position that humans are causing global warming”. But merely enumerating the strength of consensus around the fact that humans cause climate change is largely irrelevant to the more important business of deciding what to do about it. By putting climate science in the dock, politicians are missing the point.

[…]

In the end, the only question that matters is, what are we going to do about it? Scientific consensus is not much help here. Even if one takes the Cook study at face value, then how does a scientific consensus of 97.1% about a fact make policy-making any easier?

Lewandowsky and Cook believe that it will make it easier because the more people who ‘believe in climate change’, the more there is apparent pressure on government to act on it. But this is naive.

First, at least as far as the UK public is concerned, policy action has proceeded not just in spite of the public’s indifference to the climate issue, but perhaps because of its general indifference to politics. Climate change has risen up the political agenda as politics has become professionalised, and managerial in character, leaving the public with less democratic choice, and public debate deprived with contested values. The political crisis that this disinterest might cause has been largely offset by borrowing the cultural authority of science — science as a weapon. The idea of managing public affairs according to the ‘best available evidence’ always sounds good. Like ‘motherhood and apple pie’. But politics isn’t about responding to the ‘evidence’. It is about contested values about how society should be organised. A dearth of ideas to contest leaves a bloated public sector in dire straits, and so scientists are recruited to give just one message: do as they say or your children will die. Arguments for ‘action on climate change’ are invariably arguments for the accretion of power away from the demos. Lewandowsky and Cook do not argue for the ‘consensus gap’ to be closed in order that the public demand their politicians take notice; they make the argument for the consensus in order to deprive the public of democracy, whether or not Lewandowsky are aware of it.

Second, Lewandowsky and Cook miss the point that there is a difference between knowing there’s a consensus and knowing what the consensus consists of. I say they miss the point. But they do know that explaining what the consensus is, and what sceptics’ arguments are, would be to give a hostage to fortune. The political argument is invested too heavily in the science, the object of which — the natural world — has a habit of confounding expectations. Especially environmentalists’ expectations, who, throughout the second half of the 20th century, prophesied civilisation’s immanent collapse in a new way every five or ten years… Silent springs, overpopulation, resource depletion, ozone depletion, acid rain… climate change. There is still political utility in these scare stories, but there is less inclination to express a view about when they will become reality. To admit to shades of grey would be to limit the political utility.

So, sceptics, in the arguments from the likes of Lewandowsky and Cook in the debate about the consensus without an object take the form of objectless consensuses. Climate sceptics are, in the arguments of Lewandowsky and Cook, like ghosts: they are the subject of lots of stories, but they do not exist. They do not have names. They do not have ideas or arguments. They are intended only to haunt the imaginations of climate activists… To fill them with horror, rather than to face reality. The sleep of reason brings forth monsters.

Walport, Spiked

I have a short piece over at Spiked Online on UK Chief Scientific Advisor, Sir Mark Walport’s injunction that climate sceptics should ‘grow up’.

According to an article in The Times (London) earlier this week, the government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Mark Walport, is about to start a lecture tour, which ‘will put climate change back on the political agenda’. With the global effort to reduce CO2 emissions in tatters, with the EU doing a volte-face on its own green energy targets, with the UK examining its own commitment to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and to green legislation, and with scientists scratching their heads about the absence of warming over the past 17 years, Walport’s words seem incautious, possibly foolish.

The Sleeping Dragon… Sleeps

“The sleeping dragon has awoken”, says Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF).

CHINA’S 12GW SOLAR MARKET OUTSTRIPPED ALL EXPECTATIONS IN 2013

23 January 2014Last year was a record year for PV installation worldwide, with a rush of activity in China on the back of a national feed-in tariff one of the main drivers

Beijing and Zurich, 23 January 2014 – China’s solar developers installed a record 12GW of photovoltaic projects in 2013, and a booming market at the very end of the year may even have pushed installations up to 14GW. No country has ever added more than 8GW of solar power in a single year prior to 2013, and China’s record outstripped even the most optimistic forecasts of 12 months ago.

But then, China is no ordinary country. It’s massive — home to nearly a fifth of the world’s population. And the capacity of solar PV is dismal. 10%, on average. And of course, the ‘boom’ in China’s PV sector is driven by subsidy:

A CNY 1 (16 US cents) per kWh feed-in tariff for large PV projects connecting to the transmission grid ended on 1 January, creating the year-end rush. China’s National Energy Administration announced earlier this month that there were 12GW of 2013 installations, but this preliminary estimate may be exceeded.

According to this infographic, the price of electricity in China is 8 US cents per kwH. So electricity from solar PV in China costs three times as much as electricity produced conventionally. But how much is it really, anyway?

12 Gigawatts of capacity is a lot.

It is 12,000 megawatts…

or 12,000,000 kilowatts…

or 12,000,000,000 watts

But solar PV cells are only about 10% efficient. So that’s

1,200,000,000 watts.

And there are 1.351 billion people in China. So that’s a whopping…

0.89 watts of net capacity per person. And yet…

“The 2013 figures show the astonishing scale of the Chinese market, now the sleeping dragon has awoken” said Jenny Chase, head of solar analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “PV is becoming ever cheaper and simpler to install, and China’s government has been as surprised as European governments by how quickly it can be deployed in response to incentives.”

The focus on “the scale of the Chinese Market” forgets the scale of China. The Dragon doesn’t even have enough power to sit on standby mode, much less wake itself.

China, however, is, by contrast powering itself. But much debate exists about how.

Founder & CEO of Bloomberg New Energy Finance — which is part news agency, part green energy lobbying organisation, and part environmental NGO — tweeted a challenge to Bjorn Lomborg, who has criticised claims that China is leading the clean energy ‘revolution’.

Michael Liebreich @MLiebreich 2h

@Sustainable2050 And it’s only 16c/kWh. I want to see @BjornLomborg claim the Chinese should burn more coal and eat more smog instead of PV.

Lord Deben — or John Gummer, as he is affectionately known by his critics — joined in the tweeting…

John Deben @lorddeben 1h

@MLiebreich @KeithAllott @Sustainable2050 @BjornLomborg Happily they wouldn’t listen as the Chinese are following the science!

The Chinese are following the science… Says Gummer. Never mind sleeping dragons, the sleep of reason brings forth monsters.

However, a more sober news agency — Reuters — reported recently that,

China approves massive new coal capacity despite pollution fears

BEIJING, Jan 8 (Reuters) – China approved the construction of more than 100 million tonnes of new coal production capacity in 2013 – six times more than a year earlier and equal to 10 percent of U.S. annual usage – flying in the face of plans to tackle choking air pollution.

The scale of the increase, which only includes major mines, reflects Beijing’s aim to put 860 million tonnes of new coal production capacity into operation over the five years to 2015, more than the entire annual output of India.

[…]

Chinese coal production of 3.66 billion tonnes at the end of 2012 already accounts for nearly half the global total, according to official data. The figure dwarves production rates of just over 1 billion tonnes each in Europe and the United States.

A tonne of coal can produce about 2000 kilowatt hours of electricity. 3.66 billion tonnes can produce 7,320,000,000,000 kilowatt hours of electricity — or seven hundred times as much as China’s solar PV output. In other words and numbers, the 12GW of solar PV capacity added to China’s grid in 2013 was equivalent to 5.2 million tonnes of coal — around a twentieth of the coal producing capacity it added in the same year.

China’s coal use is projected to increase to nearly 5 billion tonnes by 2020.

The ‘sleeping dragon’ is not going to even open its eyes until the cost of solar PV has been reduced by at least a third, and that’s not even taken into account the costs of intermittent nature of solar power.

As I’ve argued previously on these pages, what environmentalists in general, and green energy evangelists in particular have missing is a sense of proportion.

Science and Anti-Science. Again.

Michael Mann is denying the debate again, arguing in the New York Times, ‘If You See Something, Say Something‘.

THE overwhelming consensus among climate scientists is that human-caused climate change is happening. Yet a fringe minority of our populace clings to an irrational rejection of well-established science. This virulent strain of anti-science infects the halls of Congress, the pages of leading newspapers and what we see on TV, leading to the appearance of a debate where none should exist.

Judith Curry has responded to the article, and other of Mann’s statements:

Well, I do like the title of Mann’s op-ed. Here is what I see. I see a scientist (Michael Mann) making an accusation against another scientist (me) that I am ‘anti-science,’ with respect to my EPW testimony. This is a serious accusation, particularly since my testimony is part of the Congressional record.

If Mann is a responsible scientist, he will respond to my challenge:

.

JC challenge to MM: Since you have publicly accused my Congressional testimony of being ‘anti-science,’ I expect you to (publicly) document and rebut any statement in my testimony that is factually inaccurate or where my conclusions are not supported by the evidence that I provide.

Scientist and non-scientist alike have, throughout the climate debate, struggled to identify precisely what it is they object to about counter-positions. This, it seems obvious to say, is because of the incoherence of their own proposition.

As I point out, the ‘scientific consensus on climate change’ turns out, in most instances to be a ‘consensus without an object’. Which is to say that most arguments for political action to mitigate climate don’t actually proceed from the science at all, and in many cases make up the content — i.e. ‘object’ — of the consensus to suit the argument. The claim, which Mann himself uses in the NYT, for example, that 97% of scientists agree that ‘climate change is real’ and that ‘we must respond to the dangers of a warming planet’ isn’t borne out by a reading of the survey, which was itself imprecise about its own definitions, and captures the perspectives Mann has himself dismissed as ‘anti-science’: sceptics are part of the putative ’97 per cent’. Few sceptics argue that ‘climate change is not real’.

It follows then, that their own argument being incoherent, the likes of Mann will misconceive challenges to it. Unless, that is, Mann’s rhetoric is strategic: to not let out of the bag the ‘it’s more complicated than it-is-or-it-is-not-happening’ cat. It might well be true that ‘climate change is real’. But it might not be a problem. It might well be a problem, but it might not be a problem, as it is framed, of survival vs apocalypse. It might not even be a problem that necessarily leads even to a single mortality. It might just be a big inconvenience, that drags on for centuries, but which takes nobody by surprise.

The refusal to admit questions of degree into the climate debate is a sure sign that the debate is neither as clearly divided as Mann claims, nor that science can resolve it simply. The division of the debate into binary, opposing categories is strategic, political. He might as well say it divides between goodies and baddies. He fails to accurately describe the debate he is taking a position in. And that is an even more interesting phenomenon than the discussion about who is taking which position with respect to the question ‘is climate change happening’.

Mann divides the debate into ‘science’ and ‘anti-science’. This has been tried many times. But the debate is not so easily characterised. And here’s why.

This is an ‘anti-science’ argument:

Knowledge about the world cannot be achieved through the systematic formulation and testing of hypotheses through observation and experimentation.

Here’s another:

All scientific enquiry is a sin against God.

This argument is wrong, but not anti-science:

There is no such thing as cancer.

The object of the claim is cancer, not the science which determined its existence. Taking issue with the object or finding of a scientific investigation is not the same thing as taking issue with science.

Even if someone were to claim, as Mann seems to believe is being claimed…

There is no such thing as climate change.

… it would not be ‘anti-science’. It’s not a denial of the scientific method, even if it seems to be a denial of what the scientific method has produced. Most sceptic positions in fact attempt to use, not deny, the value of science.

The mis-characterisation of the argument, however, is a denial of the scientific method. Mann believes he can rule out any objection to his argument, not by reference to either his own scientific argument, or to the argument which seemingly contradicts it, but by reference to the weight of opinion that seemingly supports it.

The argument is about authority, not about facts pertaining to the material world. If the argument were about facts about the material world — i.e. objects — the scientific consensus invoked by Mann, would have an object. Mann and his detractors would be divided over a proposition. They aren’t. Many sceptics agree that ‘climate change is real’. And many of them, and other people who have attracted the epithet ‘denier’ are scientists, doing science. Hence, Mann pretends first that the debate divides on the meaningless proposition, ‘climate change is real’, and then that it is a matter of science vs anti science.

What Mann and many others confuse is the difference between science as a process, and science as an institution.

As Curry explained recently, “Skepticism is one of the norms of science”. To deny criticism, and to refuse even to admit to the debate parameters that might let debate occur is to deny the scientific method. Mann, in attacking his detractors not through argument about the science, but by questioning their obedience to the orthodoxy, makes science a religion, like clerics accusing lesser holy men of heresy or infidelity — the claim only has gravity by virtue of science as an institution — the weight of numbers, and their affiliations — not by virtue of the claims and counter-claims having been tested.

Curry calls Mann’s bluff — he should make plain what is the scientific claim which is in dispute, but which shouldn’t be, and which are the claims in general that sceptics seemingly deny.

He won’t ever commit, however, because he can only commit to hollow propositions like ‘climate change is real’.

Countless arguments across the web and in public life fail ever to make it plain what it is they are actually about, precisely because such esteemed scientists as Mann — who want to influence politics — have not made any progress in identifying their own argument, either. More than 20 years of effort have not led to presidents or prime ministers — nor even their climate change ministers — making factually accurate statements about climate change, and especially the link between climate change and extreme weather events. The misrepresentation of the debate continues, repeated by the media, politicians, and scientists, each hiding behind the authority of institutional science.

Away from the debate that only exists in Mann et al’s heads — of one side representing the proposition ‘climate change is real’, and the other side denying it — it seems that there is a widespread view that planet has warmed, slightly. But that warmth is not as much as was expected, and a hunt has begun to find the ‘missing heat’ in the deep oceans. Moreover, attributing that warmth to human society has been harder than was expected. Furthermore, the consequences of that warmth for natural processes have been harder to establish than was expected. Even worse, the effect of those consequences on human society have not been identified at all, in spite of claims to the contrary. And finally, the effectiveness of policies intended to mitigate those non-existent effects has not been established, nor survived a robust cost-benefit analysis, much less won democratic support. Even in this very (over-) simplified view of the climate debate, these are at least five questions of degree, each of which contingent on the magnitude of the previous, but which are routinely waved away by claims that ‘climate change is real’, and that ‘the majority of scientists’ agree with the proposition, and that those who disagree are ‘anti-science’. Anyone invoking the consensus in debates about climate change are thus separated from reality by at least five degrees.

Mann urges us ‘if you see something, say something’. So we say what it is we have seen, and the reply is that what we have seen is the result of being anti-science. But science is about reconciling different perspectives, not excluding those perspectives which do not fit the political agenda that institutional science has attached itself to. If ‘seeing something’ obliges the seer to ‘say something’, it must oblige the seer to discuss it with those who see it differently, not to merely shout louder in an attempt to drown out the other perspective. Any failure to do so reveals that what the seer sees is not the product of science.

What the other perspectives variously urge, either directly or by implication, is a more thorough interrogation of the perspective that Mann et al offer. Mann wants to argue that what he sees is hard, cold, objective fact — a reading of the world as it is, uncontaminated by the fragility of the human perspective. But it’s not enough to say ‘climate change is real’. We have to agree on what climate change is, and what its consequences are. But as this blog argues, ‘climate change ‘ means many different things to many different people.

For some climate change means only some form of socialism can rescue the human race from extinction. For others it means the construction of supranational institutions to monitor and regulate global productive activity. For some it means opportunities for ‘clean tech’ venture capitalists. Whatever the material basis of Mann’s claims is, a look at the human world and the arguments about climate change should demonstrate that there is nothing simple about the ideas about society’s relationship with the natural world that are in currency, and that thus a great deal is expected of science, and is presupposed in scientific investigations of the natural world. Mann is saying more than that we can observe a rise in temperature and attribute it to anthropogenic CO2; like many others, he’s saying that there are consequences for other natural processes and for human society.

A cascade of presuppositions emerges when we try to unpack claims like Mann’s about the urgency of what they have ‘seen’. He resists criticism of those claims by lumping them in with the — uncontested, unquantified — claim that ‘climate change is real’, and by belittling his critics. The presuppositions of the claims he makes need unpacking, and they need debate as much as they need to be taken seriously by science.

By excluding other perspectives, Mann is left only with his own. If science is the process of reconciling different perspectives, such that the fragility of perspective is excluded, then by excluding perspectives, the product of Mann’s science — what the likes of Mann see — is an image of himself, passed off as a picture of the world. An angry, censorious and arrogant scientist reveals much about the prejudices that form the environmental perspective, and just as much about the politics that has invested so much in him.

Buy a Newspaper, or the Planet Dies…

Over at the Guardian, Professor of Journalism and former editor of the Daily Mirror, Roy Greenslade observes that…

The Independent is up for sale. The paper’s founder, and current chairman of its publishing company, Andreas Whittam Smith, has been authorised to seek out a buyer.

The owners, Alexander Lebedev and his son, Evgeny, have been indicating for some time that they would be happy to dispose of the paper and its sister titles, i, and the Independent on Sunday.

They have made various cryptic statements over the last six months about their willingness to offload loss-making papers that they see no prospect of turning into profit.

The decline of the Independent’s circulation was something observed on this blog back in 2009.

The post was moved by comments around this particularly alarmist headline, which epitomised the Independent’s coverage of the climate story. (With a couple of exceptions).

As alluded to in the blog post, three years earlier an article on the BBC about ‘climate porn’ by none other than Richard Black, had interrogated, albeit sympathetically, the Independent’s deputy editor on the noisy line the newspaper had taken with respect to climate change. The answers were candid, to say the least:

No British newspaper has taken climate change to its core agenda quite like the Independent, which regularly publishes graphic-laden front pages threatening global meltdown, with articles inside continuing the theme.

A recent leader, commenting on the heatwave then affecting Britain, said: “Climate change is an 18-rated horror film. This is its PG-rated trailer.

“The awesome truth is that we are the last generation to enjoy the kind of climate that allowed civilisation to germinate, grow and flourish since the start of settled agriculture 11,000 years ago.”

Ian Birrell, the newspaper’s deputy editor, said climate change was serious enough to merit this kind of linguistic treatment.

“The Independent led the way on campaigning on climate change and global warming because clearly it’s a crucial issue facing the world,” he said.

“You can see the success of our campaign in the way that the issue has risen up the political agenda.”

“If our readers thought we put climate change on our front pages for the same reason that porn mags put naked women on their front pages, they would stop reading us.

“And I disagree that there’s an implicit ‘counsel of despair’, because while we’re campaigning on big issues such as ice caps, we also do a large amount on how people can change their own lives, through cycling, installing energy-efficient lighting, recycling, food miles; we’ve been equally committed on these issues.”

But it seemed, even then, that the Independent’s readers really did think that the editors were using catastrophic images to titillate an audience. Hence, I argued, the decline in the newspaper’s readership figures, 2006 to 2009.

Thus, the newspaper would go into ‘negative circulation in Summer 2018’:

I thought I’d update my graphs. It seems things haven’t got any better for the poor old Independent.

And things aren’t getting any better for the Guardian, either.

There are of course a number of reasons for the decline of ‘dead tree media’, one of which is the rise of Internet-based media. However, the internet had been around for a decade before the series above begins, during which time sales were stable, or possibly even showed an improvement.

However, I prefer a different explanation. All newspapers have lost sales. But the Independent and Guardian have suffered more than average, and I don’t believe their catastrophism is coincidental.

This blog has long observed that the more an institution embraces the climate issue, the surer we can be that the embrace signifies a crisis of some kind, analogous to an existential or identity crisis. Political parties, trade unions, and even giant corporations have sought to attach themselves to the image of planet-saving. The newspaper resorts to climate catastrophism, not simply as some kind of pornography in order to sell copies, but to attempt to identify itself in a world it has trouble making sense of. (That’s why people buy newspapers, after all.)

This is demonstrated by taking a look back at Ian Birrell’s words. In 2006, his brief history of… erm… history was that a benign climate had ‘allowed civilisation to germinate, grow and flourish since the start of settled agriculture 11,000 years ago’, which we would be the last generation to enjoy. Equally blandly, the world might be repaired by ‘cycling, installing energy-efficient lighting, recycling’. The allusion to Nature’s Providence rules out humans as the agents in their own development: civilisation only exists because the weather was nice. The reality, of course, is precisely the opposite: civilisation exists because nature is indifferent to our discomfort, thus humans worked together to improve their condition.

Vapid accounts of human history and the forces which shape it underpin vapid accounts of the contemporary world. Such analyses become less convincing. Hence the newspapers remain on the shelf.

The shrill histrionics that pass as ‘journalism’ today reflect the authors’ own inner experiences, not a sharp focus on the world. Birrel’s naturalistic account of the world is an internal monologue, shared only by a small number of people, most of whom work in institutions that suffer the same kind of crisis. The newspaper epitomises that ideology. It is read by an increasing narrow class of people, whose ideas are shared by fewer and fewer people. The crises this causes appears to them as the End of the World, not as their own inability to make sense of it.

UPDATE

Environmentalists are keen on projections and predictions based on existing trends. In 2009, I ‘projected’ that, on the basis of the trend seen in the decline of the Independent’s circulation, it would reach only a negative number of people by 2018. What does the new data say about when the Independent and Guardian will close?

According to the linear trend, I may have been a little pessimistic about the Independent’s future.

However, the fit isn’t very neat. The polynomial trend suggests a different future…

Of course, this is fun, not science. The Guardian and Independent are no more obliged to projections based on polynomial trend lines than they are obliged to follow the Climate Resistance blog’s advice that they should relax their alarmist outlooks.

Re-Writing Mission History?

Stephan Lewnadowsky has an article at The Conversation, saying that sceptics are wrong, in their pointing and mocking of the failed Spirit of Mawson expedition.

As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words, and by now you might have seen dramatic images of passengers on stranded icebreaker Akademik Shokalskiy being rescued by helicopter last Friday after becoming lodged in Antarctica sea ice on Christmas Eve.

Lewandowsky is, of course, the defender of the environmental narrative. Key to his argument that the sceptics are wrong is a page on the expedition’s website, which seems to claim that the mission anticipated the ‘fast ice’ which came to surround them:

If one goes to the expedition’s website, their first three scientific goals (there are nine altogether) are as follows:

- gain new insights into the circulation of the Southern Ocean and its impact on the global carbon cycle

- explore changes in ocean circulation caused by the growth of extensive fast ice and its impact on life in Commonwealth Bay

- use the subantarctic islands as thermometers of climatic change by using trees, peats and lakes to explore the past

Says Lewandowsky:

In other words, the expedition is experiencing the very conditions it set out to study — namely the various kinds of sea ice that scientists know are increasing around Antarctica, while the icecaps on Antarctica are known to melt.

However, there is no mention of ‘fast ice’ on the site’s ‘expeidtion aims’ page in July last year, according the Archive.org wayback machine.

Now the expedition’s aims are outlined under a page called ‘Science Case‘, which indeed contains the reference to ‘fast ice’. But according to the Wayback machine, this didn’t appear until November, but the page in question wasn’t captured until January 2.

A Google search for the passage ‘explore changes in ocean circulation caused by the growth of extensive fast ice’ in November yields zero results:

A search for the same expression in December 2013 reveals no links that contain the passage before the vessel got trapped in said ‘fast ice’.

Lewandowsky would no doubt reject this as a ‘conspiracy theory’, but it seems to me that there is no evidence that the reference to ‘fast ice’ on which his argument rests existed before the fast ice engulfed the expedition. It is possible, of course, that my limited web-detective skills and the tools available aren’t equal to the task of proving it, one way or another.

However, further searches in various time-frames for ‘Spirit of Mawson” and “fast ice” reveal very little discussion along the lines of Lewandowsky’s claims. What little there is, contradicts it…

Days 10-18 – 17 to 24 December 2013

Commonwealth Bay And East Antarctic CoastlineWe hope to arrive at the fast ice edge in Commonwealth Bay on 17 December and commence our science work and over-ice approach to Mawsons Huts in earnest. Of course our progress will be dominated by weather considerations, but ideally we would moor the vessel against the fast ice edge so that ice and ocean studies can begin and we can send our airborne drone out to view the route towards Cape Dennison and Mawsons Huts. Once a route is determined we believe we will need to use our over-ice vehicles ( Argos) to mark a route then commence transporting scientists and passengers to the coastline as weather and ice conditions allow and the route is safe.

We also expect to move the vessel along the coast to other sites in the region such as Cape Jules, Port Martin and perhaps the French station of Dumont D’Urville.

The Spirit of Mawson’s expedition aims didn’t make the fast ice an object of study as much as it made it a mere port. Who knew that the port would become the storm? Not the Spirit of Mawson team.

Lewandowsky seems to be making stuff up again.

Science, Advocacy, Politics, Technocracy

Judith Curry and Brigitte Nerlich have been focussing on some interesting questions about scientists and advocacy. Judith Curry has quite a series on the subject, but the two posts linked to seem to have been provoked in part by Kevin Anderson’s comments urging scientists to be ‘advocates’ in some sense, but that not ‘speaking out’ is ‘more political’ than speaking out: to speak out is to be an ‘advocate of the status quo’. Here’s Kevin Anderson.

Anderson’s argument is not helped by the fact that the Tyndall Centre, where he deputy director and leader of the energy and climate change research programme, recently held a conference on ‘radical emissions reduction’, the content of which seems to be overtly political, to say the least. Here is one presentation at the conference, by Andrew Simms, who is famous for declaring that there were just 100 months left to save the planet (now there are just 35).

Andrew Simms, NEF/Global Witness, ‘A Green New Deal: historical precedent and current potential’ from tyndallcentre on Vimeo.

A problem for Anderson is that Simms’s argument is more than just ‘advocacy’. It is political. Certainly, he wants to talk about ways to respond to climate change. But Simms really wants to comprehensively reorganise the entire productive economy, to say how much each of us should have, and so on. There are many problems with Simms’s arguments. But what concerns me most is that ideas like Simms’s — such as the ‘Green New Deal’, for instance — get smuggled in under cover of “science”.

The politics on show at the Tyndall Centre’s conference has certain characteristics. First, the urgency of the climate issue is used to cement the foundations of new political institutions, like the Tyndall Centre, which place putative expertise close to policy-making. The problem should be obvious — nobody who disagrees with that compact between the academy and the state seems to have been invited to the conference. Second, the public is conceived of by the likes of Simms as an object which needs to be managed, and its behaviour and values engineered. The exclusion and objectification of the public represents a further departure from democratic politics. Rather than being advanced by popular movements, achieving their aims through the democratic process, we see influence for ideas like Simms’s being sought by an academic elite and by politicians and political institutions, outside of democratic oversight, insulated from criticism by deliberate exclusion.

Anderson is no less political:

As it stands, policy makers are either running scared of the perceived wrath of the electorate or are choosing to listen to the sceptics’ appealing messages of inaction rather than responding to the implications of the science. Similarly, business leaders fear both the ire of their shareholders and the unchecked forces of competition destroying any firm daring to go beyond incremental change. And as for the scientists, certainly there are a few brave heads raised above the parapet, candidly translating their analysis into the everyday language of politics and lifestyles. But most of us are remiss in this respect. Whilst over post-conference dinner drinks the atmosphere is of resigned melancholy, put us anywhere near a minister, CEO or journalist’s microphone and we’ll typically mutter platitudes of technological optimism and green growth.

[…]

As the religious doctrine of the Catholic Church impeded the progress of heliocentrism, so the competitive market dogma of contemporary politics constrains the free expression of academics today.

If Anderson wants to argue that it is imperative for scientists to speak out, he must at least deal with the problem that, to the rest of us, it seems obvious that the putative climate crisis is a vehicle for political agendas, for activists like him and Simms, and of course, for governments and political parties who find it difficult to connect with the public, and routinely seek ways to circumvent their own problems of legitimacy. He says that governments resist ‘the implications of the science’, but in reality, politicians saw opportunity in the climate crisis, hence they have sought to champion it. Leaving aside the technical questions around climate change, advocates of climate policy seem to be advocates of a certain forms of politics — forms of politics which we have seen before, and which have been attempted around different ecological issues in very recent history.

To put it very bluntly indeed, the eugenicists of mid 20th Century Europe and America had a moral responsibility, it would seem, to warn of the dangers of the contamination of superior races by inferior blood, through inter-racial marriages. Similarly, the Neomalthusians of the 1960s and ’70s, who are today awarded honours by the Royal Society, were compelled to warn of a world overrun by hungry black and brown people — their science told them it would happen. The results of their computer modelling were indubitable. Global institutions and global policies were needed to ensure that the individual choices made by millions upon millions of unwashed, uneducated, uncultured people from non-white races didn’t swarm and swamp the civilised nations. Science — the scientific consensus — said it was better that abject poverty persists, allowing nature to take its course, keeping otherwise uncontrollable populations in check. Policymakers dutifully obeyed. They seemed only superficially reluctant.

Whether or not ‘climate change is happening’, and ‘the implications of the science’ are as Anderson claims, isn’t it possible that the climate crisis is in fact, first and foremost, a political crisis, born out of the prejudices of that form of politics? Isn’t it possible that the role and functioning of science has changed as the relationship between the public and political institutions has changed? Isn’t it possible that science’s advocates are caught up in that change, without having formed a clear understanding of it, and the context of their own research? Indeed, isn’t it possible that the political crisis can appear to the likes of Simms and Anderson as an environmental crisis?

The context of the climate debate seems to me to have been missed out by those reflecting on the scientist-vs-advocate problem. I don’t mean it to say, ‘oh, look, science was wrong about race, population, resource-use and limits-to-growth, therefore…’, but it does seem obvious that the history of attempts to understand –and control — human society from a naturalistic perspective is not a very nice one. We can’t talk about the need to organise global productive economy around the issue of climate change until we have discussed the same order of claims that were made, in living memory, about population, resources, and race. Scratch the surface of arguments for ‘radical’ action on climate change, and you find the Neomalthusian’s arguments buried only slightly beneath. Scratch further, and find a great deal more of rank misanthropy. ‘Stop scratching’, say the environmentalists, ‘or the world will end’.

Brigitte Nerlich hints at the problem:

These recent debates make public some of the dilemmas at the heart of making science public. These are particularly problematic in the context of climate change, where speaking up, from whatever perspective and position, can lead to being shouted down, but where speaking up is increasingly demanded of scientists in particular by people in high office, such as the UK’s Chief Scientific Advisor Sir Mark Walport. The complex relationship between science, communication and policy (which is not as linear as some might think or wish it to be) and the complex relationship between science, advocacy and silence is however little understood (and quite easily misunderstood) and needs much more research. This also holds for the relationship between science and noise of course, but that’s another story.

All these recent episodes demonstrate that every act of speech and every act of silence opens up a space for interpretation and misinterpretation leading to further speech and further silence. These acts of speech and silence also open up spaces for power struggles over who should speak (for whom), who has the right to speak (about what), how to deliberate about science and politics, what the outcomes of these deliberations should be, and so on. How we use our individual and collective acts of speech and silence to negotiate common (global, national, local) goals relating to the world we live in and want to live in, still remains a deep democratic conundrum.

Meanwhile, Judith Curry works from Roger Pielke Jr’s schematic outlined in The Honest Broker:

While Jasanoff argues that Pielke’s representation is over simplified, I think it serves well to clarify this particular debate. Below is my take on [Tamsin Edwards vs Gavin Schmidt vs Judith Curry vs Kevin Anderson] in this debate:

Kevin Anderson seems to view only one role for scientists – the Advocate – whether scientists choose to engage or be silent.

Gavin Schmidt sees the choice between Pure Scientist and Advocate, whereby anyone who engages has values and is therefore an Advocate.

Tamsin Edwards is a proponent of engagement but not of advocacy, putting her squarely in Science Arbiter box.

As for moi, I engage and get involved in policy discussions but do not advocate, putting me further towards the Honest Broker box than is Tamsin.

To make it explicit and clarify, my involvement in policy discussions related to climate change is:* open up space for public discussion and argumentation

* question the efficacy of proposed policies at achieving desired outcomes and pointing out potential unintended consequences

* disclosing the limits of scientific information and the extent of uncertainty

* As summarized in my NPR interview:“All we can do is be as objective as we can about the evidence and help the politicians evaluate proposed solutions”

This is different from advocacy (although i recall reading somewhere that hotwhopper regarded my activities as advocacy against mitigation). While advocacy is somewhat elusive to define, the Wikipedia definition serves well:

Advocacy is a political process by an individual or group which aims to influence public-policy and resource allocation decisions within political, economic, and social systems and institutions. Advocacy can include many activities that a person or organization undertakes including media campaigns, public speaking, commissioning and publishing research or polls or the filing of an amicus brief.

[…]

Back to my original recommendation that scientists should steer clear of advocacy unless they are prepared to make sure that their advocacy is not irresponsible (see my previous post (Ir)responsible advocacy). And if scientists are hoping that their advocacy will be effective, then they are advised to become educated about the policy process, politics, and the relevant science and technology studies research.

The roles of Science Arbiter and Honest Broker of Policy Options are ways for scientists to engage with the public and in the policy process without being an Issue Advocate.

JC also quotes Pielke Jr’s definition of advocacy:

I argue that “stealth issue advocacy” occurs when scientists claim to be focusing on science but are really seeking to advance a political agenda. When such claims are made, the authority of science is used to hide a political agenda, under an assumption that science commands that which politics does not. However, when stealth issue advocacy takes place, it threatens the legitimacy of scientific advice, as people will see it simply as politics, and lose sight of the value that science does offer policy making.

This blog has long argued, a la Pielke, that scientific claims belie political arguments. However, the problem for the concept of ‘stealth advocacy’ might be that stealth advocacy is so very very stealthy that it is extremely hard to explain to the likes of (for instance) Anderson and Simms that they are advocates of politics/ideology/policies. It’s obvious to me (and perhaps you) that Simms’s argument is political. But perhaps it isn’t so obvious to Simms himself.

I find it hard to fault Pielke, Nerlich or Curry’s thinking on most things. But I wonder what use there is in an endless taxonomy of agents in the climate debate, and ideas about configuring effective relationships between science and governance.

Would even an honest broker have ever been able to resist eugenics and neomalthusianism? Could being objective about the evidence, and helping politicians consider the evidence have stopped the ‘limits to growth’ thesis from developing its toxic hold over (and against) the development agenda? Could public engagement have stopped 20th Century scientific racism?

The following may sound shrill, and lean towards a reductio-ad-Hitlerum argument. But notice that, even though we all now know that the racial science of the early 20th Century was political, not even the Royal Society is so aware of the difference between science and ‘ideology’ that it recognises mid 20th Century malthusianism as a racist doctrine and Paul Ehrlich as a nasty racist. The Royal Society gives Ehrlich awards instead, salvages his failed prophecies, and re-animates them to increase their own leverage in political debates about the environment. The task in front of the honest broker is bigger than he realises: it’s him versus some serious institutional muscle.

What if the racists and neomalthusians really did have the best available evidence, but, for whatever reason, that evidence was inadequate, or simply wrong? Is it good enough to be wrong for the right reasons? What if the business of collecting the objective evidence was — as we now know it was — utterly contaminated by ‘ideology’? Being objective is no guarantee of objectivity. What appears to us as objective is often subjective. If this simple fact was not true, science would neither be possible nor necessary; we would see things as they are.

What is the importance of things like climate and race to the ‘future of mankind’ that causes so much hand-wringing, such that billionaires donate huge sums of money to research institutions like the Smith School and Martin School at Oxford, The Grantham Institute, amongst a number of others, including the Tyndall Centre, to answer such questions? (Wasn’t it the same compact between uber-wealthy ‘philanthropists’ and academic scientists that led to the Club of Rome and its Limits to Growth?)

It’s obviously the case that, if we expect scientists to ‘inform’ policymaking, we create both an imperative for them to speak out, and we direct their researches, and we make the direction of that research vulnerable to vested interests and political agendas. Take, for instance, the Oxford Martin School’s mission statement:

The School’s research is helping to better anticipate the consequences of our collective actions, and influence policy and behaviour accordingly. We aim to develop new approaches to some of the most intractable questions. In fact, to be funded by the School, scholars must demonstrate that their research will have an impact beyond academia and will make a tangible difference to any of today’s significant global challenges.

Similarly, the Smith School at the same University:

The Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment is a leading international academic programme focused upon teaching, research, and engagement with enterprise on climate change and long-term environmental sustainability. It works with social enterprises, corporations, and governments; it seeks to encourage innovative solutions to the apparent challenges facing humanity over the coming decades; its strengths lie in environmental economics and policy, enterprise management, and financial markets and investment.

The Oxford Martin School (OMS) wants to ‘influence’ not only policy, but also behaviour. As is discussed above, one of the presuppositions — for better or worse — of the democratic tradition produced by the Enlightenment is the idea of autonomous moral agents participating in public decision-making, and being free to make decisions regarding their own lives in the private sphere. The public is sovereign, and can hold power to account. We can see in the newly-emerging relationships between supranational organisations, businesses, the academy and the state, an institutional shift away from those ideals. That’s not to overstate the existing influence of the Martin and Smith schools, (though it should also not be underestimated, as was recently revealed by David Rose). The point is to demonstrate the direction of travel — the form of politics which is developing, right under (or high above) our noses.

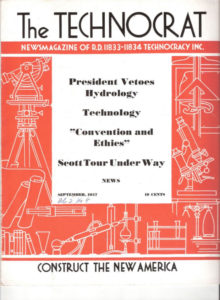

It’s also worth noting that this idea isn’t entirely new. Take a look, for example, at this journal produced by Techncracy Inc in 1937.

Technocracy is the science of social engineering, the scientific operation of the entire social mechanism to produce and distribute goods and services to the entire population of this continent. For the first time in human history it will be done as a scientific, technical, engineering problem. There will be no place for Politics or Politicians, Finance or Financeers, Rackets or Racketeers.

Technocracy states that this method of operating the social mechanism of the North American Continent is now mandatory because we have passed from a state of actual scarcity into the present status of potential abundance in which we are now held to an artificial scarcity forced upon us in order to continue a Price System which can distribute goods only by means of a medium of exchange. Technocracy states that price and abundance are incompatible; the greater the abundance the smaller the price. In a real abundance there can be no price at all. Only by abandoning the interfering price control and substituting a scientific method of production and distribution can an abundance be achieved. Technocracy will distribute by means of a certificate of distribution available to every citizen from birth to death.

The Technate will encompass the entire American Continent from Panama to the North Pole because the natural resources and the natural boundaries of this area make it an independent, self-sustaining geographical unit. Technocracy’s blue-prints have been designed for this continent and for no other. It is an American Plan for the American continent. No imported political philosophies including Democracy, are in any way applicable.

But science wasn’t quite the antidote to the excesses of ideology that it was hoped to be. And this is shown by the transformation of its advocates’ vision. The ambition of Technocracy Inc. in the 1930s was the optimal management of the productive economy. Today, the justification of technocracies is conceived of somewhat differently. In 1937, advocates of technocracy believed that scarcity had been abolished, thereby making economics redundant, whereas the basis for technocracies in 2013 is the idea that in spite of almost another century of economic, industrial and scientific development, scarcity, either in the form of substance, i.e. resources, or as natural processes such as the sequestration of atmospheric CO2, persists. At least in 1937 technocrats believed in abundance for all. Today’s miserable technocrats conceive of economics as merely insufficient to mitigate against scarcity. Science does not transcend its historical context quite as efficiently as its adherents claim, indeed, in many senses, it more precisely reflects the prejudices of political elites — the ‘Politics or Politicians, Finance or Financeers, Rackets or Racketeers’ — than even the politicians, financeers do themselves.

In our heads, we all want a technocracy to abolish politics and economics. Right, Left, or Centre, we all believe that ours is the most efficient way of organising public life and productive activity, which, free from obstacles would deliver the best of all possible worlds. We should therefore not rule out the technocrat’s fantasy of efficient management too hastily. What we should criticise is the technocrat’s desire for political organisation – that society can be managed according to a single, uncontested and uncontestable design. Advocates of ideas about how society should be organised should be committed first to the idea that those ideas should win influence, stand up to hostile criticism, and be made legitimate by popular assent.

In other words, a technocracy might well be legitimate, just as long as we all wanted it. (But then, of course, it wouldn’t really be a technocracy). Consider this…

Technocracy, Inc., realizes only too well that no political government on this Continent has either the courage or the structural facility to institute a Continental Health and Medical Service as proposed in the blueprint of The Technate of America, which includes in part, compulsory physical examinations of all citizens every six months; the application of preventative as well as curative medicine in diseases, etc.

A compulsory physical examination, every six months… It would be a wonderful thing if there were sufficient resources (i.e. we were all rich) for medical examinations every six months. But I deny completely that it would be a Good Thing if we did it, either voluntarily or by force. For the majority of us, it’s simply not necessary. Such frequent and unnecessary interventions might, moreover, be damaging, physically, as well as psychologically, since such regular contact and monitoring would provoke anxiety and passivity about our own health. The price of deference to expertise is a bloated technocrat and the subjugation of autonomy. The idea of compulsory medical examinations gives the game away: it sounds like a great idea that will promote health, but it means you don’t own your own body. Never mind debates about private property and its institutions; Technocracy Inc. wants to own you, body and soul.

The appeal of technocracy is, of course, only that it does away with politics. That is a desire shared by thinkers across the political spectrum. But science as the negation of politics denies the virtue at the heart of both.

But neither science nor politics proceed by excluding different perspectives. Both exist and proceed because of, not in spite of, different perspectives. Were it otherwise, science and politics would neither be necessary nor possible. But technocracy abolishes competing accounts of the world: it says that hoi-polloi is not competent, either to form a view of the world, or to make decisions about their own lives or public matters; and as the climate debate shows, unofficial interpretations of The Science are waved away as so much ‘motivated reasoning’ and the such like. In short: the desire to eschew politics and to replace it with science makes science political. It is ideological. It is as ideological as any “ideology” ever was. The result is the actual negation — denial — of science, the process of discovery. The purpose of science becomes instead efficient management.

And this is what Anderson is really driving at with his concerns that ‘the competitive market dogma of contemporary politics constrains the free expression of academics’. It’s BS, of course — academics have rarely ever been so free (and the electorate rarely so disengaged), yet he privileges ‘academic expression’ over the democratic expression of the wider public, who he frames in terms of their slavish obedience/lust for the promises of the market. Moreover, academics have rarely ever been so sought by political power to legitimise it. What seems to be bothering Anderson is that this transformation of politics has not been total enough. We should see this transformation reflected in the difference between the claims made by technocrats in the 1930s and their descendants today: whereas the earlier technocrats declared the era of scarcity to be over, today’s technocrats promise only to deliver us from doom. Technocrats could not persuade anyone with promises of the most efficiently organised society, so technocratic ideas formed instead around the necessity of technocracy. Whereas the critics of capitalism in the 1930s promised more than capitalism (albeit without freedom), Anderson can only articulate an alternative to what he perceives as free-market capitalism (it isn’t) in terms of disaster, catastrophe, Armageddon. Climate change can’t just be a problem that could be managed within any number of political systems — it has to be a total, encompassing, terminal crisis, that mandates a particular response: political environmentalism.

And this is what is missed in attempts to define a proper public role for scientists in public life. A bit like asking where the banjo player should sit in a chamber orchestra. Or worse… A kazoo player. It would be obvious to anyone with an ear that they are out of place. That’s not to say that there is no place for banjos, kazoos — or scientists — in public life (though I cannot think what they might be), but that the idea of them being essential is one ultimately borne out of the immediate problems of politics, not out of the necessity of public policy. This is not to say that expertise has no business in politics. Parliaments and other public institutions have always been able to call on expertise for information, evidence and advice. It is to suggest, however, that debates about the anatomy of honest brokerage, or to devise codes of ethics for scientists, may miss the point. There is insufficient reflection in debates about the climate about the scientisation of politics.

The rebuttal, of course, from the technocrats is that the world will end without them, and that anyone who argues otherwise argues with the whole of science (or at least the consensus). But this argument takes its premise as its conclusion: that the world is this hostile place, which demands optimal management. It is from this ideological premise that a lot science is advanced. The notion of the Earth as a collection of systems in fragile equilibrium on which society is closely dependent, for instance, forms the basis of a great deal of policy as well as research into ‘climate impacts’. This in turn encourages the idea that any changes in natural processes are in fact destruction, attributable to human economic and industrial development. Yet as hard as scientists have searched, no ‘tipping point’ has been established, and no optimums identified — they are instead presupposed to exist.

It should be obvious that Kevin Anderson, and many others, whether he knows it or nor, is doing more than science, and that the Tyndall Centre — amongst many other research organisations — has a political agenda, in spite of claiming to be working objectively.

So, rather than asking for a more clearly defined function for science, might it not be more productive, to admit to the debate the idea that science without politics is, for the moment at least, an impossibility, and that our understanding of the natural world is soaked through with political ideas, and has been to a greater or lesser extent since classical antiquity. Rather than excluding the objects of ‘advocacy’ from expert scientific advice to politics, might it be better to argue in the first instance for scientists to say that the questions and expectations of it need closer scrutiny.

In order to understand ‘what science says’, we need to be clear about what it has been told. Scientists are not going to stop being advocates, and the expectation of scientists to transcend advocacy, ideology, or politics is an expectation of science that it has demonstrated WRIT LARGE that is not yet equal to. However, we can interrogate the values, claims and ambitions of expert and lay environmentalists, independently of the science. Take for example, this nasty little piece in today’s Guardian by Alex White:

Should Australian newspapers publish climate change denialist opinion pieces?

Should Australian newspapers, like Fairfax, publish opinion pieces that deny or seek to cast doubt on man-made global warming?

[…]One of the arguments that I have seen against the notion that climate denialists should be given a media platform is that without it, there would be no “balance” in reports on climate change.

However, surely newspapers should aim for objectivity rather than balance, especially if one “side” is just plain inaccurate.

After all, what appears on newspaper opinion pages is a decision made by editors. Newspaper editors decide every day what merits inclusion in those pages; completely fanciful views are effectively banned through the decision not to publish rubbish.

Is the responsibility of major media publishers on honesty, accuracy and objectivity?

That seems to be the view of the L.A. Times, and of Reddit.

Does Fairfax have the same responsibility? Should it have published the McLean opinion piece?

White poses censorious statements as questions. And behind those statements are implications about individuals’ capacities to make decisions about what they read for themselves, and the freedom that they should be entitled to, to form opinions for themselves, even if they end up contradicting ‘science’. All of which makes White’s desire for censorship more extraordinary, given his profile at the same paper:

Alex White is a leader in progressive campaign strategy, communications and social marketing, with over a decade of experience with unions and non-profits.

When did ‘progressives’ become so, erm, ‘liberal’ with the notion of press freedom? In the past, progressive movements were perhaps the loudest critics of appeals to putative objectivity in public matters, and fought against the regulation of the press. It was widely understood that seemingly objective claims about the material world were often, at best, premature. But now ‘science’ is being used to make arguments to limit what newspapers may publish, by left wing and environmental activists like White. We could wait for the honest brokers to say “but that isn’t science”, and that all the scientific evidence in the world cannot tell you about the rights and wrongs of limiting the freedom of the press. Or we could make the observation ourselves.

Too much emphasis on science is, in many respects, the problem. If it isn’t science, it doesn’t need a scientist to point it out. If scientists are advocates, then the debate is predominantly political, not scientific, and honest brokers may find themselves with very little to say. We might learn more from looking more closely at the descent of White and his kind from ‘progressive’ to authoritarian than we might from looking at charts depicting the extent of sea ice in the poles.

What is Science?

The previous post here made the point that the IPCC serves much less to inform debate than as a vehicle for any number of political ambitions or prejudices, few of which can be justified on the basis of the IPCC’s reports — assessments of what ‘science says’.